The Power of Liszt: A Celebration at FIU

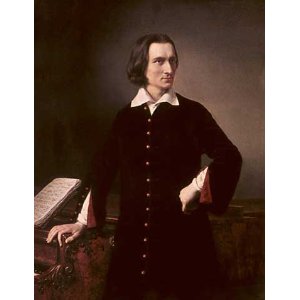

Tonight and tomorrow (Oct. 27 and 28) mark the first two concerts in Miami to be sponsored by the new Florida International University chapter of the American Liszt Society, which is dedicated to advancing knowledge about Franz Liszt, the great Hungarian pianist and composer.

The bicentenary of Liszt’s birth in 1811 falls next year, and there will be many performances of his music across the world to mark the event. But here’s hoping a lot of rarely heard pieces get an airing. Liszt wrote a tremendous amount of music over the course of what was in those days a rather long life (he died at 75 in 1886, three years after his son-in-law, Richard Wagner), and it would be wonderful to hear the things that never seem to make it to concert halls.

Thanks to the generosity of people who share their recorded rarities with the world, there is much Liszt on YouTube, including what I’m listening to as I type, which is the Benedictus of the Coronation Mass, written in 1867. It’s lovely and quite straightforward, and goes some way to affirming the pull of the religious life on Liszt, who combined a career of gigantic celebrity and scandalous love affairs with the taking of minor orders in the Catholic Church.

Much of the better-known music of Liszt I personally find problematic, and that includes the big B minor Sonata, which I’ve always found impressive but not persuasive, even when it’s peerlessly played. And a lot of his earlier piano pieces seem to stop just as they get going, as if he were making the musical case for attention deficit disorder.

But there’s no gainsaying the breadth of his genius, and the huge impact he had on music generally. He is the inventor of the piano recital, the creator of the tone poem, and a master of cyclic form. More importantly, his late music looks so far ahead harmonically that it served as a test road for the compositional explorers who came afterward.

The two FIU concerts are set for 7:30 tonight and tomorrow night at the Wertheim Performing Arts Center. The first program contains solo, chamber and vocal works by Liszt and his contemporaries, including Liszt’s song Es muss ein Wunderbares sein, the Hungarian Rhapsody No. 9, and two movements from his piano transcription of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique. Also on the program are pieces by Chopin, Wagner, Alkan, Carl Tausig, and Dvorak.

The second features the Croatian-born pianist Kemal Gekic, a fine player, in the First Piano Concerto and the Totentanz. Gekic will be accompanied by the FIU Symphony and conductor Grzegorz Nowak. On the first, solo half of that program, Gekic will play the Hungarian Rhapsodies No. 10 and No. 11, two of the Legendes (St. Francis of Assisi and St. Francis of Paola), and the well-known Funerailles. These concerts present an ideal opportunity to reassess the legacy of Liszt, which it’s fair to say isn’t recognized by the general public at large. I’m fond of a line from David Dubal’s memoir (Evenings with Horowitz) about the pianist Vladimir Horowitz, in which the two discussed this. “I must tell you that Liszt was the greatest of them all in the piano. We cannot even estimate how high he is,” Horowitz told Dubal.

We can’t really estimate Liszt’s contribution as a composer either, because so much of his huge output isn’t routinely played or known. Perhaps FIU’s new Liszt chapter will go some way toward widening our understanding of this seminal musician.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·