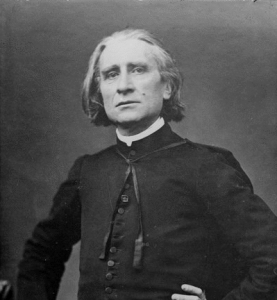

Happy 200th, Franz, with love from FIU and UM

On Saturday, the classical music world marks the 200th birthday of Franz Liszt, born Oct. 22, 1811 in the town of Raiding, then in the Hungarian part of Austria-Hungary and today a town in eastern Austria. Liszt has a complicated legacy, and today it’s primarily his innovations for the piano that make his reputation, including his invention of the piano recital. Before Liszt, pianists always played as a part of a musical hodgepodge in concert, following a singer, say, and then in turn being followed by an orchestra.

The first performance in 1830 of Chopin’s First Piano Concerto, for instance, featured Chopin and the orchestra for two movements, after which there were selections for horn and soprano before Chopin returned to play the finale of his concerto. But Liszt insisted on having a program all to himself, and, given his prowess and sheer animal magnetism, he got few objections.

But he also was a major composer, even though his reputation today in this regard is problematic. Scholarly consensus seems to be that most of his larger pieces are uneven. I’ve been listening to his oratorio “Christus,” for instance, and the first couple movements are ravishing, with beautiful, colorful orchestral writing and a marvelous use of old-school-style polyphony from the chorus that makes the music sound timeless and new at once.

But then things bog down a bit, led by a static “Stabat Mater,” and while I ended up adoring the piece and wondering why it is that no courageous choral director won’t take it on, there is some justification for the claim that the bulk of the music doesn’t move along enough and tires listeners out. Yet Liszt wrote so many other things that we should be hearing more often, such as his songs, that I hope the anniversary sends more people back to the collected editions to find good stuff.

In the meantime, we’ll be celebrating his work with the piano, which is the most durable part of his output. Earlier this month, I heard the young French pianist Guillaume Vincent play the Sixth Hungarian Rhapsody in an encore at his concert in Delray Beach, and I couldn’t help thinking what a delightful piece it is if you can pull it off. But it’s almost never played in concert.

Instead, we hear the canonic Liszt, such as the Sonata in B minor, and while there’s something to be said for exploring unusual Liszt, at least because of the birthday we can hear the great works more frequently.

Tonight and Saturday at FIU, for instance, Liszt is being celebrated in two concerts. Tonight’s event includes lieder and chamber music by Liszt and his contemporaries, though details weren’t available when I asked. Saturday night, the fine Croatian-born pianist Kemal Gekic solos with the FIU Symphony in the Second Piano Concerto (in A) on a program that also includes a true rarity: the “Fantasy on a Motif from Beethoven’s ‘Ruins of Athens.’”

Also tomorrow night, the fine American pianist Jerome Lowenthal pays tribute to Liszt with a program that includes the Sonata in B minor and selections from the “Annees de Pelerinage,” such as “Venezia e Napoli.” Also on Lowenthal’s program is the Petrarch Sonnet No. 104.

On Oct. 28, FIU again hosts an all-Liszt event with pianist Misha Dacic, a familiar face for local concertgoers. Program details weren’t available, but on Sunday afternoon in Boca Raton, Dacic will play an all-Liszt recital that shows a most adventurous approach. In addition to the “Dante” Sonata and the “B-A-C-H Fantasy” (originally for organ), Dacic has chosen the Dumka from the “Glanes de Woronince“ collection, the “Grosses Konzertsolo” and “Le Triomphe Funebre du Tasse.”

One hopes Dacic brings that same program to FIU on the night of the 28th, or one close to it. Because while Liszt has long been regarded as one of the immortals, it nevertheless remains that, for most people, the whole scope and range of Liszt’s writing is completely unknown. That’s unfortunate, but his birthday provides a good reason for enterprising minds to sift through the works of Liszt and find the hidden gems.

Here’s hoping that one day more people are generally aware of the huge contribution Liszt made to his art and to the times he lived in. No time like his bicentenary to find out.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·