A Witness in Exile: an interview with poet Brian Spears

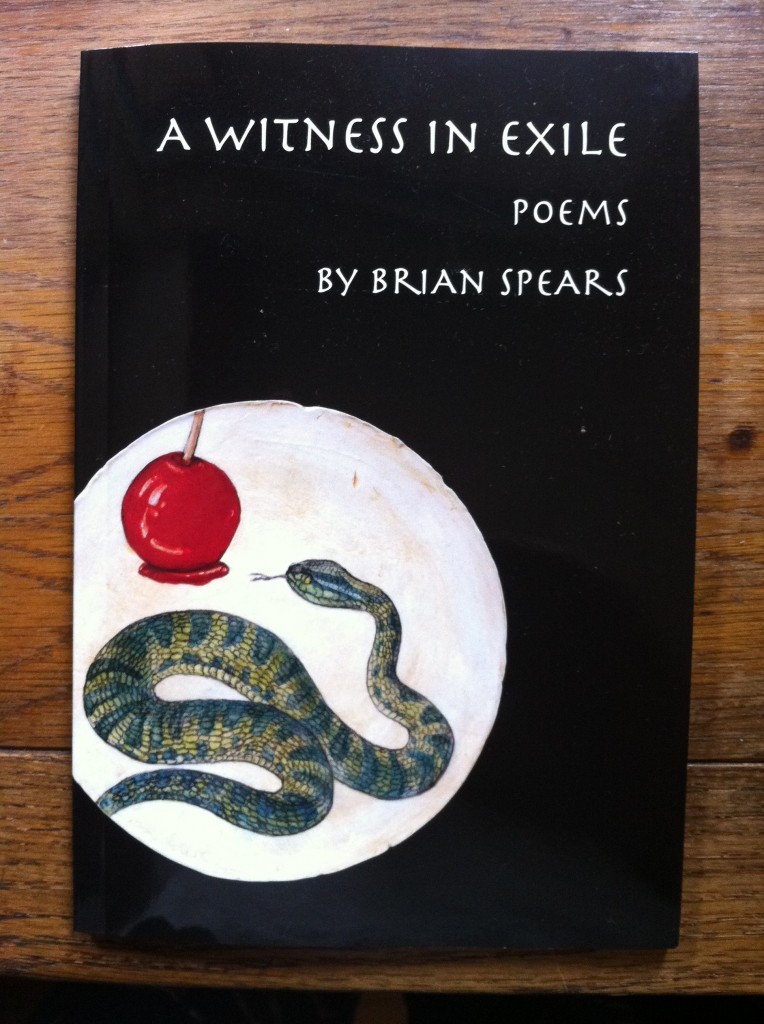

Even though we only live 10 miles apart, I first met teacher, poet and The Rumpus poetry editor Brian Spears on Facebook. Where else would two poets meet? Brian Spears, like many of us, has lived an interesting life. He is a former forklift driver, Wal-Mart floor waxer and insurance, furniture, home electronics and automobile salesman. Currently, Spears teaches literature and creative writing at Florida Atlantic University but plans to move this summer to Iowa to take on new adventures. Spears just published his first collection of poems, A Witness in Exile, which is a book grounded in his exile from being a Jehovah’s Witness, and from his father and family. I spoke with Spears about the process of writing the poems for his book and the underlying theme, his exile, that tie it all together.

Neil de la Flor: Tells us the back story: what was the impetus for your book?

Brian Spears: There really wasn’t one, at least in the book sense. I just wrote a bunch of poems, threw some out, wrote some more, threw some out and so on until I had a book. My second manuscript is a conceptual project, and the poems I’ve started writing for my third are, in very general terms, about the way my body has started to betray me as I go through middle age, but A Witness in Exile is very much a conglomeration of poems from the last seven years or so of writing.

ND: Are you still a witness in exile or have you come in from the woods?

BS: I’d say I’ve moved through the woods into a new place. I’ll always be exiled from the Witness part of my life because their demands for re-entry are far more than I’m willing to pay. One of the nice things about this book for me is that I feel like I can stop writing about it some. At one point about five years ago, I felt like every poem I wrote had to do with the Witness experience. But I haven’t written one since I decided on the final poems to go in the manuscript. The last Witness poem I wrote was “The Elder’s Son.”

The elder’s son has left the church doesn’t preach from door to door. The elder doesn’t talk to his son anymore. (An excerpt from “The Elder’s Son” by Brian Spears.)

ND: I’ve asked you this question before but in what ways did growing up a Jehovah’s Witness influence your writing and in what ways?

BS: I have to give the Witnesses this—they read the Bible a lot, and they’re very attuned to symbolism. It plays a big part in their theology, so when I started reading and writing poems in high school, I instinctively knew that images had power and that you could play with meaning in really intricate ways. What I’ve rebelled against, though, is the notion that there’s only one proper way to interpret a particular set of symbols. I prefer ambiguity, the potential for multiple paths into and out of a text. I say that even though I think a number of my poems are probably a little too over-determined.

ND: What makes a poem personal and too personal?

BS: This is a hard question, because I think it’s completely subjective to the reader. For me, it’s never the subject matter—it’s about the tone that the poet takes toward it. A poem that begs for sympathy is too personal. A poem that’s honest can be about the most intimate moment of a person’s life and not be too personal.

ND: Were you born to be a poet or were you created?

BS: A little of both? There’s a creative streak on both sides of my family—writers, musicians, artists—but I was lucky that in my high school, I fell in with a creative crowd, and while I had no talent for drawing or music, I could play with words a bit. And when I went back to it in my mid-twenties after my divorce from the church and my wife, I got some important encouragement from my teachers and my friends.

ND: Please select your favorite poem from the book and tell me why?

BS: “Jubilate Patro” is probably the one, and I think it’s because the form allowed me to explore parts of my relationship with my dad that I hadn’t been able to before, at least not in poetry. The poem just came together so naturally as I wrote it that it only took a minimum of editing and revising, and it’s the only poem I’ve ever written that I get choked up while reading aloud. And it still surprises me that I do, since I’ve read it a bunch and I wrote it about three years ago. I know what’s coming and it still hits me, and that’s why I love it.

ND: Any new projects down the pike?

BS: I mentioned the poems about middle age above, and I’m very interested in exploring the world of handmade books, letter presses, that sort of thing. I’ll have a whole new place to explore and write poems about as of this summer, since my partner, the writer and artist Amy Letter, just accepted a position as assistant professor of fiction at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa. Place is such a huge part of my work that the new home is undoubtedly going to find its way in, especially the winters. I’ll be learning to shovel snow at the tender age of 43. Hopefully, I’ll be learning how to slip a neighborhood kid a twenty instead.

ND: What don’t we know about Brian Spears?

BS: I always feel like the under-educated, under-read person in practically any conversation about poetry or art or writing. I come out of those conversations just hoping I didn’t sound like Captain Obvious.

Brian Spears book, A Witness in Exile, can be purchased at www.amazon.com. To reach Spears visit his blog at www.brianspears.wordpress.com.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·