Opera under the spell of Georgia O’Keeffe’s Skies

By Sebastian Spreng, Visual Artist and Classical Music Writer

It’s no secret: every summer, under the incredible skies immortalized by Georgia O’Keeffe, opera flourishes in the desert of New Mexico. This has occurred fortunately and punctually for the last fifty six years, a feat that must be credited to visionary New Yorker John Crosby (1926-2002). The infallible combination of unusual offerings, world premieres, repertory classics, high quality productions and established and emerging international opera stars make the Santa Fe Summer Opera Festival a Mecca for audiences from all latitudes. The setting – the Sangre de Cristo Mountains – rivals in splendor with the acoustically superb 2,100-seat outdoor theater. Performances begin at sunset (not to mention the customary previous tailgate opera picnics) and the clever programming makes it possible to attend three operas in one weekend or the festival’s five production in one week.

This summer, Puccini’s Tosca and Bizet’s The Pearl Fishers were joined by a Strauss homecoming and two remarkable rarities: the world premiere of the critical edition of Maometto II by venerable Rossini scholar Phillip Gossett and the Viennese Arabella, which marked the company’s return to Richard Strauss operas. If Vienna and Santa Fe might share any resemblance, it’s in the importance opera holds for its residents, a phenomenon in a city of 70,000 people in the middle of the desert on a 7,500-feet-high plateau.

Sixth and last of the incomparable Strauss-Hofmannsthal partnership, the plot inconsistencies of Arabella are justified by the composer score and its intermittent peaks of rapturous lyricism, which elevate it to the level of its major siblings. And if it’s wise – maybe pointless – not to engage in revisionism, Tim Albery opted for a meticulous yet somewhat glacial production, one in which Tobias Hoheisel’s gray sets suggested a hopelessly crumbling empire and contributed to the overall feeling of remoteness. Luca Pisaroni as Rossini’s Maometto II, photo by Ken Howard

If most of the cast was new in their roles, the required golden Viennese polish seemed to elude the excellent lineup of singers. Well equipped to become an important Arabella, Canadian Erin Wall played a most adequate lead, rightly supported by Mark Delavan, a rural, poised Mandryka who stressed the character’s roughness. As Zdenka, Arabella’s sister, Heidi Stober provided one of the highlights of the evening, while Kiri Deonarine acquitted herself in the vocal fireworks of Fiakermili. Tenors Zach Borichevsky (Matteo) and Brian Jadge (Elemer) both shone in their roles, and veterans Victoria Livengood and Dale Travis, as the women’s troubled parents, rounded out effective performances. Though faultless, Sir Andrew Davis’ conducting did not quite conjure up enough Straussian glow to leave an indelible impression.

Although King Roger premiered in Warsaw in 1926, this was, paradoxically, only the second time it was fully staged in the United States; the first was in 1988 at the Long Beach Opera, and the continental premiere at Buenos Aires’ Teatro Colón in 1981. Hermetic, exotic, tortuous, fascinating, laden with multifaceted dualities, symbols and mysticism, it works as a purifying ritual by depicting the protagonist’s struggle with himself, an internal turmoil that rocks his life and kingdom. For once, sunny medieval Sicily darkens, overcast with the Kafkian angst that runs through Szymanoswki’s luxuriant musical maze dotted with distant echoes of Schreker, Debussy and Scriabin.

Not too far from Pasolini’s Teorema, the disruptive appearance of a Dionysian shepherd at the court of the tormented King of Sicily triggers events that lead to his eventual enlightenment. As the opera’s hero, and main reason of the production, Polish baritone Mariusz Kwiecien confirmed his emblematic Roger. He owns the role and enriched it with dramatic and vocal naturalness; however, his constant use of vocal forte deprived the character of wider expressive subtleties. Soprano Erin Mosley (as Roxana, his wife) and Dennis Petersen (as Edrisi, his faithful counselor) matched him and Miamian tenor William Burden (as the Shepherd), displayed a notable vocal evolution, showing a welcomed heroic luster.

Director Stephen Wadsworth, conscious of the task of literally introducing the opera to an American audience, did not allow himself to be tempted by excess (as Warlikowski in Paris, and to a lesser extent, David Pountney in Barcelona) instead he chose to explore the narrative and complexity of the characters arising from the composer’s dark polyphonic tapestry. Wadsworth left open questions to the audience and sensibly unified the three acts into one, sketching a triptych of sorts – Byzantine (I), Oriental (II) and Greco-Roman (III) – that, much like a feature film, allowed the public to witness the development of the central character in less than 90 minutes. The crowning touch was provided by the opera’s chorus and versatile orchestra, remarkably conducted by young Evan Rogister, definitely a name to watch.

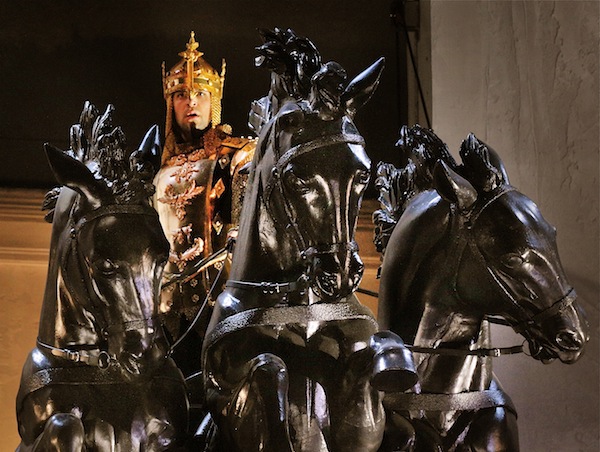

Luca Pisaroni as Rossini’s Maometto II, photo by Ken Howard

The newly restored original score of the Neapolitan Maometto II of 1820 (a distant sort of Romeo and Juliet in which Rossini appears to turn George Bernard Shaw’s incisive definition of opera “tenor and soprano want to make love and are prevented from doing so by a baritone” into “bass and soprano want to make love and are prevented by a tenor”) is a daring glorious fresco the composer revised for Venice (1822) and later adapted into French as The Siege of Corinth. Led by a formidable quartet of soloists, it’s a monumental ensemble piece in which “the Swan of Pesaro” delights himself with a succession of beautifully crafted ensembles, leaving not even room for the audience’s uncontainable applause. The amazing first act terzetone was just an example.

This virtual battle in which Montagues and Capulets seemed replaced by East vs. West, is dominate by the sultan Maometto II, a fierce conqueror, and certainly, a nearly unconquerable one from a vocal point of view. It was Samuel Ramey’s emblematic role in the 1980s and had been the dream of Luca Pisaroni, who as a teenager admired the American’s performances at La Scala. The magnificent young Italian bass-baritone not only acquitted himself in the terrifying initial Sorgete, sorgete, and subsequent killer arias and vocal pyrotechnics; he also succeeded in every facet of this complex character. At the end of the night it was obvious that Pisaroni inherited Ramey’s mantle (A noble and complete artist, he also sang a group of Schubert Lieder rendered with superb insights at the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival).

The Santa Fe Opera, photo by Ken Howard

At his side, young soprano Leah Crocetto proved to be a rising star of privileged means. Agile and splendid in the upper range, she took a while to warm up and gained ground as the performance progressed, especially from the sublime prayer Giusto ciel in tal periglio on. Another great surprise was tenor Bruce Sledge, whose big, clear voice displayed flexibility and shine. Perhaps on a off night, the only weak link in the quartet was mezzo Patricia Bardon, whose strange timbre and coloratura did not live up to the demands of the role, though she earned the audience’s applause with Non temer d’un basso affetto.

Under the stylish baton of musical director Frédéric Chaslin, the Festival’s new musical director, and the opera chorus forces directed by Susanne Sheston, David Alden’s staging added another successful element to an unforgettable night. Often criticized as extravagant and over-the-top, Alden delivered a sensational yet restrained production. Framed by the clever and massive elegant sets and eclectic costumes by John Morrell, he resorted to the well-aimed coup de théâtre (e.g., the hero’s All invito generoso in a chariot drawn by gigantic black stone horses) to dazzle the audience and legitimize Rossini’s undeniably grand opera, one that preannounce early Verdi.

In sum, three nights of high-quality opera once again made the Santa Fe Festival the obligatory destination for opera lovers in the torrid American summer. It is an exemplary undertaking worth of imitation. Bravo.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·