Three auspicious revivals at New York’s Metropolitan Opera

By Sebastian Spreng, Visual Artist and Classical Music Writer

Neither the vicissitudes of the season opener – Eugene Onegin – nor James Levine’s eagerly awaited return in Così fan tutte, nor the American premiere of young Nico Muhly’s controversial Two Boys managed to overshadow the New York Metropolitan Opera’s revival of three opera productions that in the second week of the season prevailed on their own, well-earned merits.

Bellini’s Norma has to be seen live to fully grasp the difficulties of a role as immense as it is merciless. It demands the singer’s all, especially in a venue as enormous as the Met. Very few sopranos, if any, can do justice to this masked Gallic Medea, the apex of the bel canto repertoire. It’s not necessary to run through all of her illustrious predecessors to conclude that Sondra Radvanovsky met the challenge successfully. Her achievement at the Met means she has arrived, and deservedly so, though not without some reservations. A self-assured, good-looking actress of imperious bearing, she has, above all, a powerful, enormous voice, along with the rare virtue of being able to soften it admirably (Casta Diva was her best). Nevertheless, her metallic timbre at the high end of the register exhibits a harshness that doesn’t quite please sectors of the audience. On the other hand, some famous Normas have had voices that could be considered an “acquired taste.” Radvanovsky is one of them. Photo by Marty Sohl

Though some expressive and vocal aspects of her performance still need polishing, Radvanovsky’s debut in the role (rising star Angela Meade takes her place October 24 and 28) deserved a new production. Instead, John Copley’s 2001 staging shows its age, both conceptually and visually. Kate Aldrich played Adalgisa with thorough honesty, taking advantage of the matte tone of her voice in clashes with her rival. She failed to rise to Radvanovsky’s level, however, whereas Aleksandrs Antonenko, playing Pollione, matched her volume with no effort. Graced with a stentorian, sparkling, powerful delivery, the Latvian tenor – who recently played Verdi’s Otello under Riccardo Muti – stirs controversy, but was nonetheless a luxury as the Roman proconsul. Veteran James Morris – once a great Wotan – sang a routine Oroveso, marred by his wide vibrato.

Fortunately, Riccardo Frizza proved again to be a first-rate bel canto conductor who stressed the link between Glück and Verdi that Norma represents, and the Met orchestra responded optimally. The young Brescian is another star on whom the Met is counting to carry on its Italian repertoire tradition. Meeting expectations, he successfully supported and rounded out the work of Radvanovsky’s new and promising American Norma.

In contrast to the former, in the other two revivals staging and design played starring roles, competing with the high-level of music making. The Tim Albery-Antony McDonald production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and William Kentridge’s The Nose are prime examples of visual esthetics in the service of music, capable of converting neophytes into devotee of their composers, even though they are atypical works, very different from two’s more established operas as Peter Grimes and Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk.

So as not to lag behind other opera houses in celebrating Benjamin Britten’s centennial, the Met revived its 1996 staging of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, one that retains its freshness. A beautiful homage to Howard Hodgkin’s paintings, Albery’s production could not have been more British or more faithful to the spirit of the libretto and the music. McDonald’s simple, ingenious, colorful, magical set design was matched by his equally imaginative costumes. Another key element was James Conlon, a seasoned Britten conductor who meticulously and impeccably sketched in sound the ambiances of Britten and Peter Pears’ 1960 adaptation of the Bard’s comedy.

Contributing to the production’s success was a solid cast led by an excellent quartet of lovers – Joseph Kaiser, Michael Todd Simpson, Erin Wall and Elizabeth DeShong – plus the stupendous Iestyn Davies as Oberon and Kathleen Kim as Titania. Special mention should be made of Matthew Rose and his “rustic troupe,” which displayed a sauciness not often seen in opera. Despite the enormous venue, Albery and McDonald’s delicious version of this intimate work exuded close-up charm and innocence.

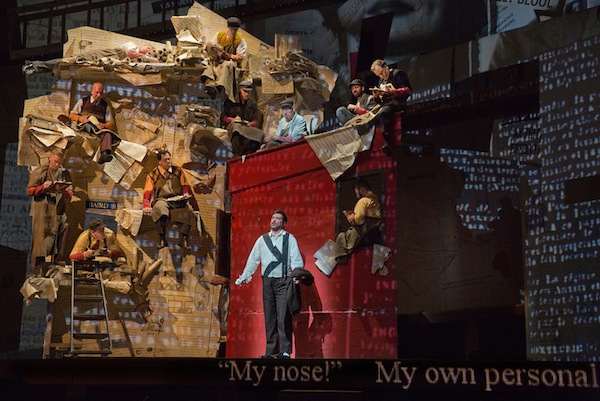

More than The Nose, it’s worth losing one’s head over William Kentridge’s production of the young Shostakovich’s opera prima. It is, quite simply, an instant classic. Seldom do we see a better amalgam of opera pit and stage, and seldom does an artist design a set that screams his personal style while enhancing the virtues of the music. Called an “anarchist grenade against the regime’s bureaucrats,” the opera, with all its creaks and squeaks, foreshadows the caricatures of the ballet The Bolt. Combining rigor and a prodigious imagination, the South African artist elevates the acerbic score, which is a perfect pairing of Shostakovich’s music with Gogol’s story of the same name.

A story with cinematic elements – 12 scenes in three continuous acts – ambitious, eclectic, rough, grating, sarcastic, but also refined and perceptive, Shostakovich’s cryptic piece can be interpreted in several ways. Kentridge opted for an oversized yet succinct framework and made use of all available visual resources (emulating Shostakovich, who fused musical styles), and produced an indivisible union reminiscent of Tatlin, Rodchenko, Meliès and Soviet constructivism. It’s an elaborate clockwork mechanism, so claustrophobic, Kafkaesque and humorous that it would dazzle its very creator. Kentridge’s Nose is a perfect little jewel that makes you wonder what the artist could do with works such as Petrouchka, Die Frau ohne Schatten, Mahagonny, Bluebeard’s Castle or, speaking of Gesamtkunstwerk, any Wagner. The good news is that Kentridge is already working on another opera, scheduled to open at the Met in 2015: no less than Alban Berg’s Lulu.

In the musical department, those same compelling contrasts were handled in his usual, natural manner by the very busy Valery Gergiev, who stressed the work’s chamber-music and symphonic elements. The nasality – as appropriate as it is ruthless – of the vocal tessitura worked in favor of the intrepid leads – Andrey Popov, Alexander Lewis, Sergey Skorokhodov and Brazilian baritone Paulo Szot (playing Kovalyov) – and a cast of veterans that included Barbara Dever, Maria Gavrilova, Michael Myers and Vladimir Ognovenko.

To sum up, in three felicitous revivals, the Met reawakened the mythical Norma, recalled Britten’s ambiguous world and rediscovered a lost nose irresistibly “found” by the brilliant Kentridge. Their success is auspicious: it cannot but encourage the theater to try out new offerings.

*On Saturday, Oct. 26, The Nose will be broadcast as part of the series Live in HD.

Photo by Ken Howard

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·