Glimmerglass shines under Francesca Zambello

By Sebastian Spreng, Visual Artist and Classical Music Writer

Every summer, in a theater on a green hill an opera festival takes place, one in which performances are preceded by picnics on the grounds. It’s not in Europe and it’s not called Bayreuth or Glyndebourne, but Glimmerglass. One hundred percent American and in every way more accessible than the others, the festival on the shores of Lake Otsego is named after James Fenimore Cooper’s fictional Lake Glimmerglass, inspired by that body of water. The author of The Last of the Mohicans was a famous resident of nearby Cooperstown, in western New York State.

For opera buffs, Glimmerglass is becoming an increasingly popular destination thanks to attractive, refreshing programming that enables patrons to enjoy four productions – in addition to other events – every weekend during July-August at the Alice Busch Opera Theater, a cozy 950-seat venue surrounded by woods and meadows. The theater’s opening in 1987 was a milestone in the festival’s continuous growth since its inception in 1975 with a modest La Bohème staged in the local high-school auditorium.

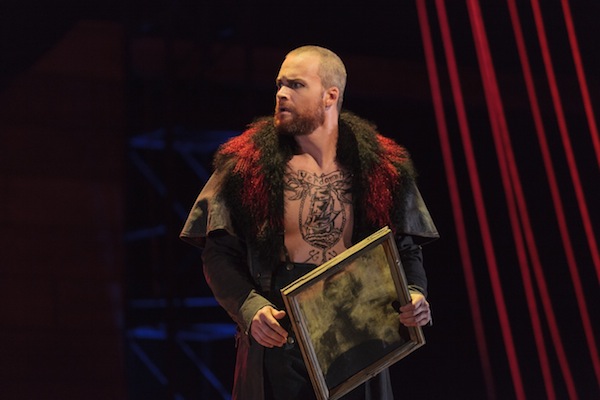

Since becoming the festival’s artistic and general director three years ago, Francesca Zambello (who is also artistic director of the Washington National Opera) has undertaken an ambitious change of direction that is palpable at every level. The festival is no longer just about opera. Zambello stages a musical every year, in keeping with her plans to expand into other genres – in this case an autochthonous one – and attract new audiences. She has also added recitals, conferences, art exhibits (including, this year, a remarkable one on the American Romantics of the Hudson River School at the Fenimore Art Museum) and an exemplary Young Artists Program of surprising quality that rounds out nicely the festival’s lineup of new and veteran opera stars. Ryan McKinny as the Dutchman in The Glimmerglass Festival’s The Flying Dutchman. Photo: Karli Cadel

The beguiling 2013 season left nothing to chance. It did justice to the three opera greats – Wagner, Verdi and Britten – honored this year, as well as to the chosen musical and an unusual pair of one-acts that contributed to the variety and originality that characterize the festival.

Boasting uniformly excellent casts, two operas – The Flying Dutchman and King for a Day – written early in each composer’s career and premiering only a few years apart, brought to light a powerful Wagner, directed by Zambello, and a minor Verdi, enhanced by Christian Räth’s direction and Kelley Rourke’s hilarious English adaptation, which more than justified the risky change of language and historical period.

In her spot-on treatment of Wagner’s first great opera, Zambello took the middle road between tradition and risk, with brilliant results. In James Noone’s set design, composed of a forest of twisted ropes, the threads of fate intertwined so as to strangle the obsessed protagonist, the impressive soprano Melanie Moore as Senta. The ropes buttressed a visually fierce set, with its contrasting colors and suggestions of underlying eroticism, and lent the production the humorous touch that also lurks behind Wagnerian solemnity.

Trapped among – and even illustrating – the sails, the ghosts of previous Sentas surrounded the excellent Dutchman played by Ryan McKinny, a young American baritone to watch, one who reminds a great predecessor and countryman, Thomas Stewart. For his part, Jay Hunter Morris (Siegfried in both the Met’s and before the San Francisco Opera’s Ring cycles, the latter under Zambello) was a stentorian Erik, and Peter Volpe, a Daland who played with the humor and implicit self-interest of the bride’s father. Thanks to an intense stage vitality (most evident in the “spinners” scene, like automatons working on imaginary spindles, and in the third act’s choruses, energetically performed by members of the Young Artists Program), you don’t miss the usually larger choir or notice the reduced size of the orchestra conducted by John Keenan.

In contrast, King for a Day relied on the unmistakable Rossini touch evident in the young Verdi’s score, here transplanted to the Swinging Sixties, and in an ending that fulfilled the premise of bringing back to life this nearly forgotten comedy of errors, performed with clockwork synchronicity by an admirable ensemble.

Alex Lawrence’s outlandish “king” and Ginger Costa-Jackson’s acrobatic Marchesa vied to steal a seamless show that, under the expert baton of Joseph Colaneri, the festival’s new music director, revealed a little-known Verdi of unsuspected effervescence and humor.

An unusual set of staged vocal works, titled Passions, included, first, Jessica Lang’s staging of Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater in a sort of tableau vivant that combined a stark stage á la Salvador Dalí with a Martha Graham aesthetic to show off the vocal-choreographic duo of soprano Nadine Sierra (an eloquent Mary) and rising countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo under Speranza Scappucci’s diligent baton.

The number was paired with a David Lang’s heartbreaking Little Match Girl Passion in an expanded version that added a choral prelude, When We Were Children. Conceived and directed by Zambello, the staging transformed Hans Christian Andersen’s tale into an intense Christmas ritual, following the structure of Bach’s passions and reverberating ad infinitum with the contributions of soloists and the community children’s choir, another experiment that seems to be turning out well.

Watching a performance of Lerner and Loewe’s Camelot with no sound amplification provides a unique experience for audiences used to Broadway, especially when it stars singers of the stature of Nathan Gunn – an anguished Lancelot – and David Pittsinger – an exceptional King Arthur – both seduced by Andriana Chuchean’s charming Guenevere. It’s impossible to leave out Jack Noseworthy’s evil Mordred heading up a cast that sang and danced with admirable ease in an appropriately minimalist set and under the direction of Robert Longbottom, with James Lowe as musical director.

For the scheduled Richard Wagner-Richard Strauss concert that framed the stage productions, the svelte Lise Lindstrom replaced Christine Goerke, who was forced to cancel for health reasons. The powerful soprano, already a well-known Turandot (she sang In questa reggia as an encore), is shaping up as a major Brünnhilde. Together with members of the Young Artists Program, she sang several lieder and performed scenes from Tannhäuser, Lohengrin, Der Rosenkavalier, Tristan and Isolde and The Valkyrie. It was a vocal tournament that stamped the seal of approval on the laboratory that is Glimmerglass, a status that was confirmed with the celebration of Benjamin Britten’s centennial, which included a wide range of compositions by the group intelligently directed by Sara Widzer. On both occasions, the performances of Julia Mintzer, Jennifer Root and Deborah Nansteel, also a good Mary in The Flying Dutchman, deserve special mention.

As an “extra added atrraction,” no less that the Honorable Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a noted opera fan attending the festival for the second time, delivered a substantive lecture on “contracts in opera plots,” followed by the audience Q & A. It was the kind of small luxury that earns this sparkling festival in the idyllic Hudson Valley the well-deserved name of Glimmerglass.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·