David Lynch at PAFA is a filthy froth of unconscious desire and fear

The atmosphere of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) is as viscous as it is visceral – at least for the time being. Since mid-September, PAFA has been taking a look back at the long visual history of filmmaker, painter and all-around artistic anomaly David Lynch. By examining the past and present of Lynch’s sprawling creative output in “David Lynch: The Unified Field,” curator Robert Cozzolino provides the first major museum exhibition of the artist’s work. The show seeks to reveal a relatively clear picture of Lynch’s elaborate vision – if anything about Lynch’s subject matter and imagery could be called ‘clear’ or ‘unified,’ that is.

On the first floor, we are initially ushered into what marks Lynch’s crucial crossover between painting and the moving image: “Six Men Getting Sick.” Having spent his time in the late ’60s honing his work as a painter, Lynch made the leap from pigment to ‘moving painting’ – a shift that is recognized for its impingement into the rudiments of cinema, and for which Lynch subsequently gained much of his notoriety. It includes elements of figurative relief sculpture and a loop of animated shapes, color fields, hands and dripping liquids, all of which give energy and transience to otherwise fixed media. The piece also demonstrates Lynch’s ongoing perception of the banal and the grotesque as intertwined. Not only does he experience this dualistic nausea as indicative of (sub)urban life, as part and parcel of institutional involvement (see also the accompanying painting: “P.A.F.A. Is Sickening”), but as integral to the creative process.

David Lynch, “Boy Lights Fire.”

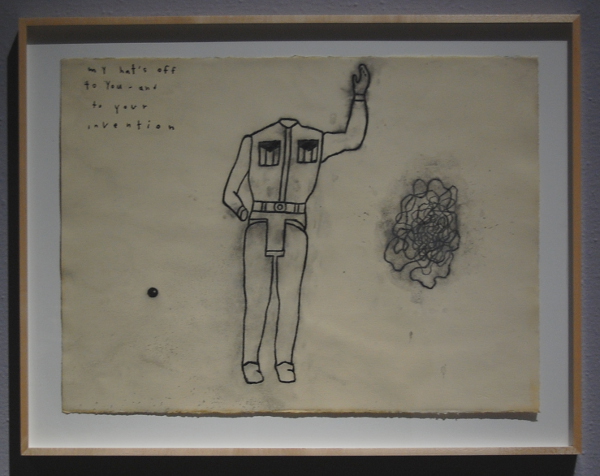

A profound surrealism hangs over the entire show, which would be expected by anyone who has seen films such as his infamous “Eraserhead.” Surely taking cues from the likes of Yves Tanguy or Salvador Dalí, few of Lynch’s characters here are biologically sound beings. Instead, they are either thickly sketched distortions of people, or deformed hybrids bearing likeness to amoebas and tree trunks as much as humans. Sometimes his figures possess unwieldy, long arms (such as in “Boy Lights Fire” and “Holding onto the Relative”), or they’re missing hands or heads (as is the case in the action figure-esque “My Hat’s Off to You and to Your Invention”).

David Lynch, “My Hat’s Off to You and to Your Invention.”

Whether well-endowed or deficient, the humanity of these individuals seems to play second fiddle to their abnormalities, and possibly their behaviors and emotions too. In a few instances, such as the heavily narrative “Mister Redman,” he even constructs curtains as a veil between our conspicuous and latent selves or as a separation between audience and action. It is truly not hard to see Lynch’s directorial eye amidst his static images.

David Lynch, “Mister Redman.”

Just about everywhere the paint and graphite are applied with gusto. Lynch does not shy away from impasto or heavy-handed marks, and the entire exhibit pulsates with excess. Although somewhat more reserved, his earlier drawings bleed with ink, like Ralph Steadman illustrations. Meanwhile, his later paintings from the 1990s onward pile oil paint, found objects and insect corpses into heaping masses of material that lie somewhere between the obscured mind within and the roiling cornucopia of life without, both unconscious and clawing to survive. The gaping orifices and stretched wires of “A Figure Witnessing the Orchestration of Time” emphasize the instinctual reptilian brain clinging to the sentient being, while compositions like “Rock with Seven Eyes” indicate an interest in anthropomorphism and the line between the conscious and inanimate – a place where death not only occurs, it somehow lives.

David Lynch, “A Figure Witnessing the Orchestration of Time.”

If there is anything underlying the tenuous threads that connect the mundane and the outlandish, it is the ludicrous. Lynch orchestrates his household brand of horror with a subtext of humor that is at once perpetual and peripheral; as soon as one attempts to stare it down, it shrinks into the background. This hide-and-seek absurdity pervades nearly every work, but disguises itself as perversity, violence and vomit… but not always in that order.

David Lynch, “Rock with Seven Eyes.”

An obvious example is “My Head is Disconnected,” a simple tempera-on-panel piece in which we are met with the savagery of decapitation, and the subsequent silliness of observing one’s own levitating (in this case rectangular) cranium.

David Lynch, “My Head is Disconnected.”

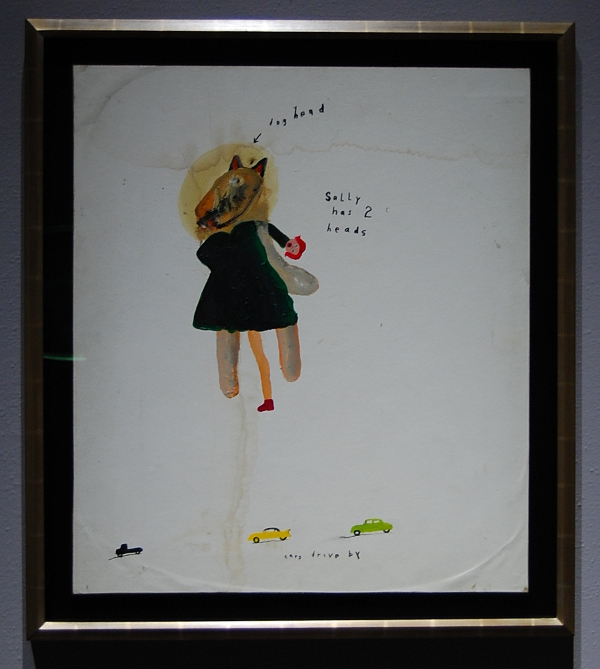

For a counterpoint of surplus instead of inadequacy, there is “Sally Has 2 Heads,” where we find a creature more dog than woman, whose secondary human head dangles behind her like a wagging tail or an extra arm. Lynch not only denotes the dog head with text and an arrow (he revels in textual instruction, almost across the board), but also goes out of his way to caption three unrelated cars driving by instead of directly referencing Sally’s hominid head. By duping us in this way, Lynch turns an abomination into a gag instead of a spectacle, proving that his powers of misdirection are as honed as his abilities to devise layers of ambiance, environment and situation.

David Lynch, “Sally Has 2 Heads.”

When confronting David Lynch’s mind on such a cavernous scale, one must not only suspend disbelief in regards to the scenarios and images presented, but of the man himself and his mythos. There is surely a level at which Lynch cannot break through his own psyche enough to directly discern his inherent desires, fears, fortitudes and failings, but the result of his attempt to do so is a body of work that uncovers a remarkable sense of unity in the filth. “David Lynch: The Unified Field” will be on display through January 11.

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts is located at 118-128 N. Broad St., Philadelphia; 215-972-7600; pafa.org.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·