Black farmers past and present celebrated at African American Museum

Agriculture has been the backbone of the United States since its inception and well before. Sprawling tracts of land tilled by tireless farmers is an image ingrained into Americana. Without their knowledge and labor, there would be no way to feed so many people across the far-flung corners of North America. The African American Museum in Philadelphia, a Knight Arts grantee, is currently celebrating the lesser-known faces of farming who have faced adversity and hardship above and beyond toiling in the fields. A pair of exhibits “Distant Echoes: Black Farmers in America” by photographer John Ficara and “Syd Carpenter: More Places of Our Own” highlight the African American agricultural world and the specific challenges and triumphs of these shrinking communities.

The photography project completed by John Ficara between 1999 and 2002 speaks volumes to the often overlooked lives of black farmers from their work, to their families, their legal battles, to their land. Perhaps most importantly, it puts faces to the names while it tells their tales through images of daily work and rest, equipment and produce.

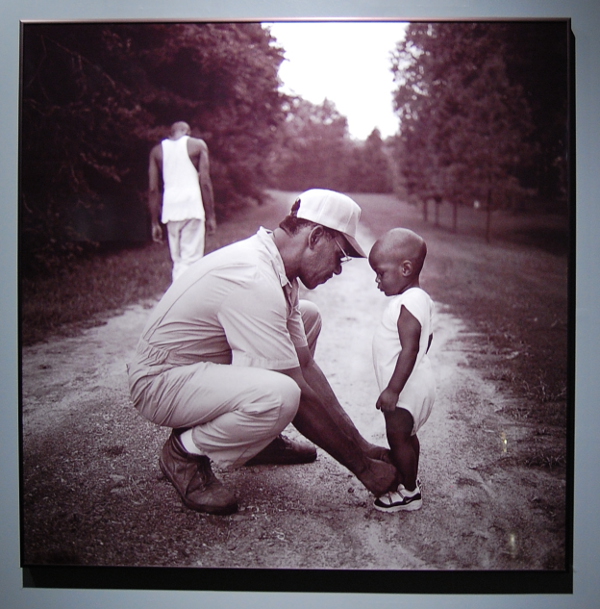

In one image, Louden Marshall ties his grandson’s shoes while his son Louden III walks away down the gravel trail. Recently having informed his father of his decision to leave the family farm that the elder Louden inherited from his father, there is a certain tension in the photo as Louden III turns his back. While the eldest says that he likes to farm despite the low income – he can be his own boss and lead in independent life – the rifts of time are still widening.

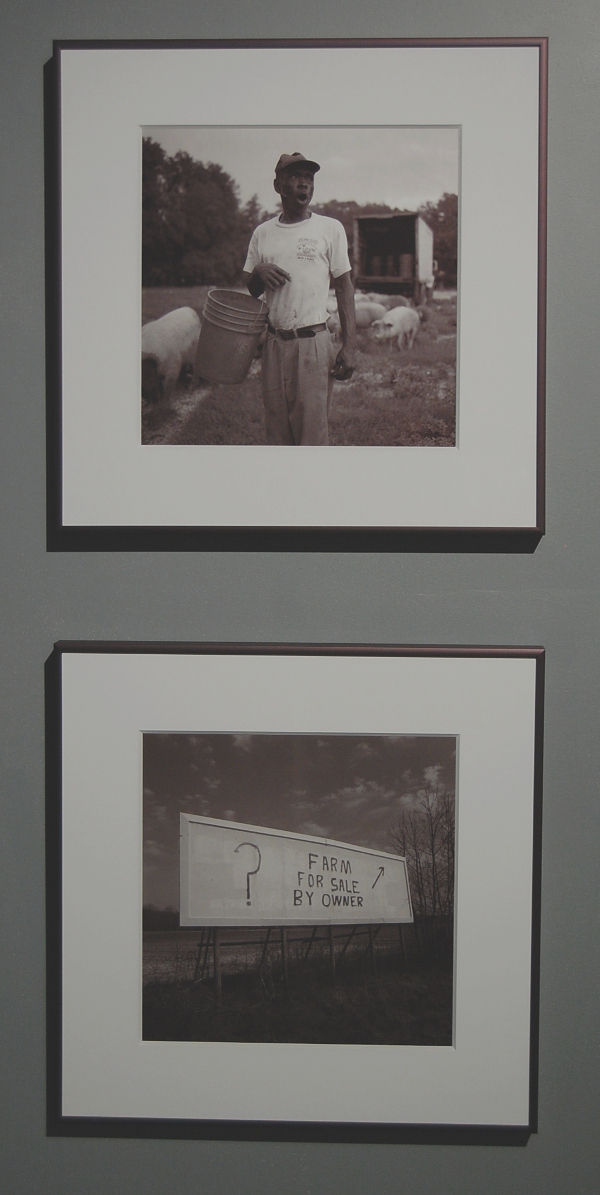

John Ficara, Top “Joe Haynes calls hogs for feeding, 2001. Warren County, Florida.” Bottom “Farm For Sale by Owner, 2000. Halifax County, North Carolina.”

Ficara tells us that, in 1920, 14 percent of farmers in the United States were African American, yet by 2003 less than 1 percent of the nation’s farmers were black. Citing failures of legislation all the way back to the rescinding of Special Field Order No. 15 by President Andrew Johnson in 1865 (which ensured each freed black man 40 acres and an army mule), the rising costs of supplies and the foreclosure of their land has led to many black farmers closing up shop.

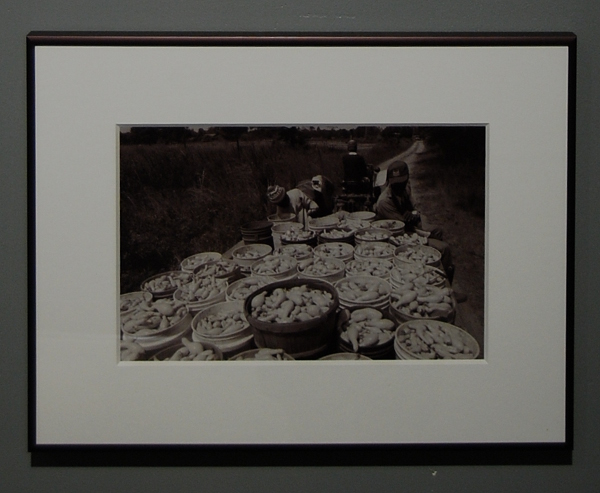

John Ficara, “Hauling harvested yellow squash.”

Many of these farmers talk about historical ties and family property, but this foothold is quickly slipping as evidenced by “For Sale” signs and a dwindling, aging demographic. The Land Loss Prevention Project petitions for the return and retention of property while some wait for compensation from a 1999 settlement with the USDA, but it appears that black farmers are fated to disappear, and with it their living cultural legacy. If the life of a farmer is one of struggle, then that of black farmers is unfathomably rigorous and oppressive.

Syd Carpenter, “Freewoods Farm.”

Syd Carpenter takes a more expressive stance to Ficara’s documentary photographs with her bulbous steel and clay sculptures that depict African American farms and gardens. Molding pieces of wooden chairs, glass bottles, and piles of grain into amalgamations of what she saw on her trips through South Carolina and Georgia, Carpenter, in her own way, creates scenes much like a documentarian, except for the abstract slant.

Syd Carpenter, “Everelena Cannon.”

Like monuments to the southern farmers with roots in Africa, these sculptures are symbolic as much as they are biographical. In “Freewoods Farm,” we find a basket, a wagon wheel, and a rifle stacked atop each other and ready to topple. Sometimes the works, especially the ones hanging on the wall, skew more abstract than representative. For “Everelena Cannon” it is easy to pinpoint some wooden rungs of a ladder and maybe some fabric or a wishbone. Otherwise, the piece all attaches to a thick, rounded form in the center, with balls that are almost too spherical to be eggs rolling off its sides. Is that pie crust to the left? Are those slabs of stone? Cookies? Mushrooms?

Syd Carpenter, “Rashid Nuri, Living Well Farms.”

Surely these fixtures are meant to convey not just a realistic picture of objects and ephemera, but also the mood of the subjects and the feelings evoked by the places they live. Despite their solid, heavy appearance, these assembled parts of people, places and things are relatively fluid as well. Each piece seems to fold in on itself, and over again, until the twisting structures combine into one mass that is loosely narrative in form, but largely an appeal to the senses.

Ficara and Carpenter disseminate the hidden lives of America’s black farmers, and their strategies together illustrate, from different angles, a past and present that deserves to be seen. Without storytellers and creators such as these, African American farmers may have simply faded away, but whether or not they vanish forever, they will not be forgotten.

Both shows will be on display through August 17.

The African American Museum in Philadelphia is located at 701 Arch St., Philadelphia; 215-574-0380; aampmuseum.org.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·