Tyler Kline flirts with flaws in transcendence at Rebekah Templeton

When one speaks of the Platonic Solids, it would be easy to assume that all depictions of these three-dimensional objects would truly be solid, but that answer is a little too simple for Tyler Kline. For his solo show “Continuous Warlock Integers” at Rebekah Templeton Contemporary Art, Kline seeks to rethink the vision and purpose of these Euclidean forms that, in recent history, have found most of their popularity through their use as Dungeons and Dragons dice. Although there is nothing wrong with a good role-playing game, Kline hopes to update these forms with fresh perspective for the future.

Tyler Kline, “The Garden of Forking Paths.”

Around the perimeter of the gallery, we find a mixture of flat, two-sided panels mounted perpendicular to the walls and a series of tall, skeletal structures coated in mottled pastel paint. The hanging works greatly resemble ‘for sale’ or ‘open house’ signs in their double-sided, 2D configuration, except for the abstract ideas they convey. With names like “Schrödinger’s Cat” and “The Garden of Forking Paths,” these plaques seem to provide enigmatic frames of reference from disciplines as wide-ranging as quantum mechanics, astrophysics, Jorge Luis Borges stories, and other lofty concepts. Pitching his artworks in this way, Kline’s real estate game is more one of thought experiments than property values.

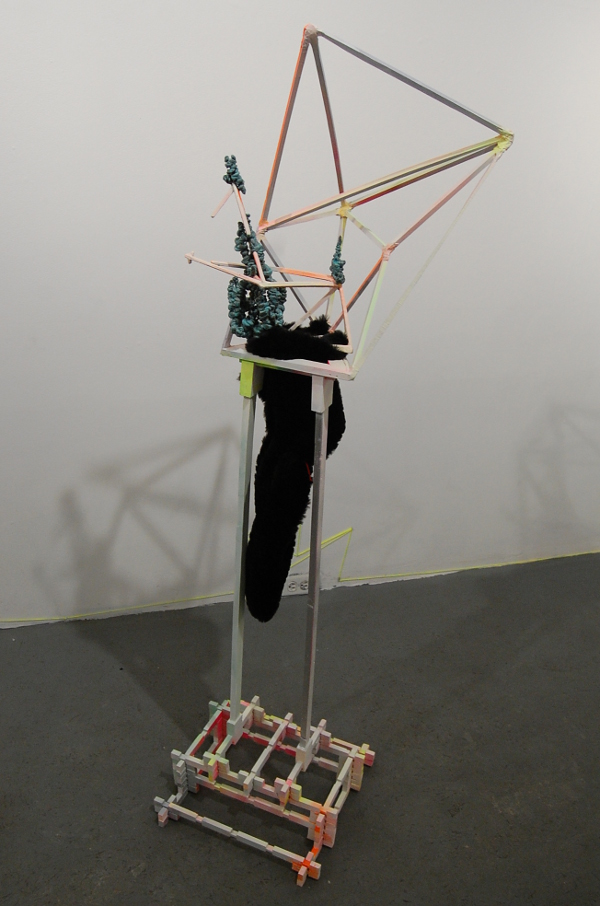

Tyler Kline, “Idaean Dactyls.”

This signage actually consists of carved woodblock reliefs used for printmaking, with the flipsides painted in amalgamations of geometric shapes. Within the inverted woodblock scenes we find one with a corridor and vanishing point in black, and elsewhere a wavy distortion of melting magenta waves. Some of the painted sides were utilized by Kline for a stop motion/digital video mash-up bearing the same title as one of the panels: “In Praise of Zombie Mediums.” Kline himself certainly subscribes to this notion, wrangling a sometimes puzzling combination of materials into his mathematically transcendent, yet often ramshackle products.

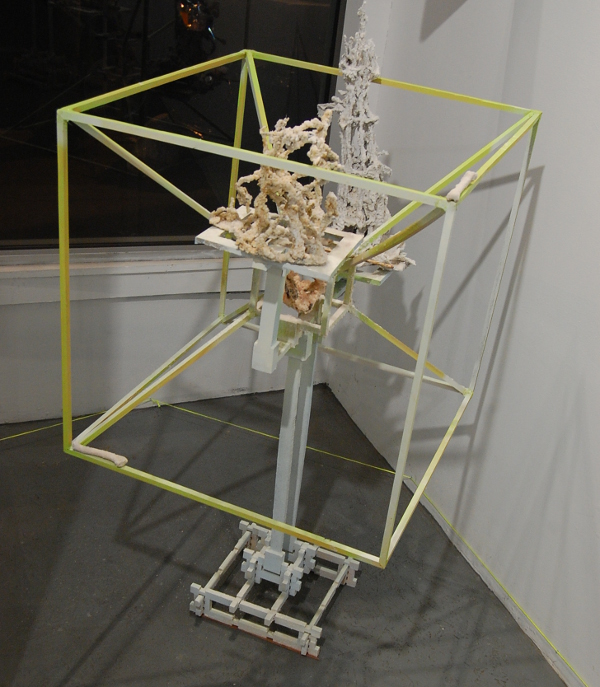

Tyler Kline, “Dodecahedron, Turtles all the way Down.”

Resting on the floor, the sculptures that divide the flat images from one another defy the duality of their companions by branching out into scaffolds that raise the Platonic Solids onto literal and proverbial pedestals. These top heavy busts are variously draped with fur, decorated with bronze and aluminum, and coated with salt as if exalted by way of some arcane ritual. At the dawn of the 21st century, this fine line between science and awe, mathematics and mysticism, seems to be Kline’s guiding principle.

Tyler Kline, “Hexahedron, the impossibility of being Square.”

Interestingly, the solids themselves are a bit lost in the fray, occasionally obscured by superfluous trusses and connections that have no apparent link to their subject. Furthermore, the faces of these forms are absent in every case; Kline constructs only the edges, leaving the sides as open space. As if subverting perfection while simultaneously holding it aloft, the artist instills every piece with a healthy skepticism familiar to any scientist or explorer. These empty objects also bear a strong resemblance to digital 3D wireframes, slipping even more dissonance between the physical and the perceived.

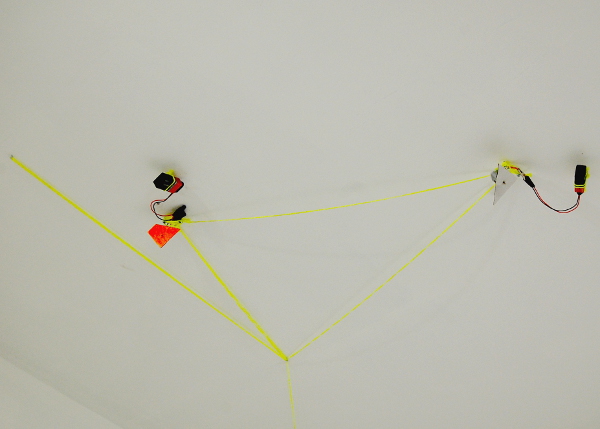

Tyler Kline, “The Complicated Futility of Ignorance.”

Unable to miss the opportunity to pull a Duchamp, Kline also slings a bright yellow strand of twine flush across the walls of the exhibit, sometimes overlapping itself in triangles near electrical outlets and in the corners of the room. On the ceiling, the terminus of this journey is a pair of spinning painted shapes connected to nine-volt batteries. By the end of the opening reception, these tiny rotating motors had ceased, their batteries depleted. With this meandering, ephemeral strand connecting everything here, we find the conclusion of the exhibit to be one of reverence for the present moment, as well as acquiescence to the muddled chaos of the universe.

By redesigning objects of supposed perfection and veneration, Tyler Kline aims to reveal a more honest notion that underlies not only Sacred Geometry, but perhaps the unassuming parts of life as well. When every moment is seen as a cacophony of indivisible instants and innumerable interconnected cycles, even a boring day can be filled with enormous significance and even the grandest ideas can be brought down to earth. “Continuous Warlock Integers” will be on display through April 25.

Rebekah Templeton Contemporary Art is located at 173 Girard Ave., Philadelphia; 267-519-3884; rebekahtempleton.com

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·