Photography from previous eras a current passion for Knight Arts Challenge winner Letter16 Press

Photo: Gallery Ehva in Provincetown, Mass., where “There Was Always A Place To Crash” was unveiled in July and some of Al Kaplan’s photographs were exhibited over the summer.

As far as cultural art centers go, Miami is a relatively new participant in this circle. But that doesn’t mean Miami has lacked artistic talent throughout its history; it’s just that much of that talent was never documented or recognized.

Recently, a number of groups and organizations have been trying to rectify that omission, including Letter16 Press, a recipient of a 2014 Knight Arts Challenge grant. To call Letter16 an organization, however, is a stretch; it’s a two-man labor of love from journalist Brett Sokol and designer/photographer Francesco Casale, whose mission is to painstakingly restore 35 mm prints from unsung photographic heroes, print them in oversize hardcover books and display them in exhibits.

“It’s great that Art Basel has brought attention to our scene here,” says Sokol, who has written about the arts in South Florida for numerous local and national publications. “But we thought, a lot of talented artists have also been pushed off of the stage” because of their age or the pre-digital materials they used. “We thought it was important to shine a light on them.”

The two zeroed in on photography, particularly photography that straddles the line between art and photojournalism. For the first project, they focused on the works of Al Kaplan. A native of New Bedford, Mass., Kaplan graduated from high school in Miami, and then returned to New England to start snapping the rapidly changing world of the early 1960s. He would wind up back in Miami by the late 1960s, where he picked up, among other clients, the City of North Miami.

But it was the years that he captured the burgeoning bohemian life in Provincetown, on the tip of Cape Cod in Massachusetts, starting in 1961 that first fascinated Sokol and Casale. The gay and straight, multiracial world that was coalescing in this small seaside town would be a harbinger of much broader social change that was coming to America, and Kaplan caught it on camera, in black-and-white. According to Sokol, the images are more than documentary evidence of a bygone era–they are intimate artistic portraits. “These were his friends and lovers. He lived that world,” Sokol says.

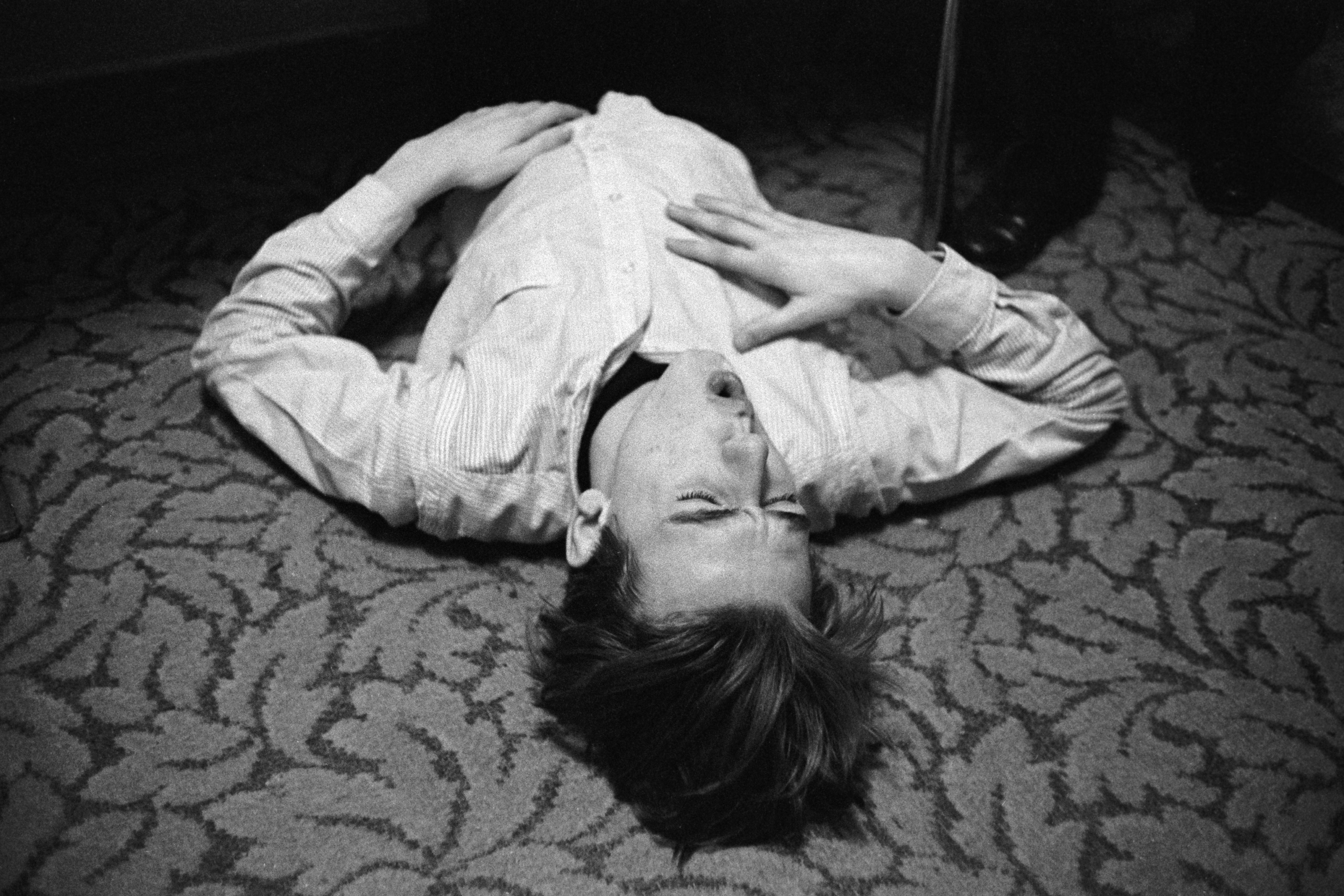

Rene Ricard in January of 1963, photographed by Al Kaplan. From the forthcoming book, “There Was Always A Place To Crash: Al Kaplan’s Provincetown 1961-1966.”

That world included Rene Ricard, who would go on to be a “star” at Andy Warhol’s Factory, and later an art critic. Another in Kaplan’s sphere was an early gay-rights activist and torch thrower, Prescott Townsend, in whose communal tree house also lived provocateur filmmaker John Waters. These are the people featured in Kaplan’s photos, many of which make up the first book from Letter16 Press: a 72-page book to be released in September, titled “There Was Always a Place to Crash: Al Kaplan’s Provincetown 1961-1967.”

In fact, in a nice stamp of approval for this first project, Waters wrote the jacket-cover blurb for the book: “Here’s the book that proves what I only remembered; yes, I lived in a tree fort in Provincetown in 1966 and inside is an actual photo of it. The benches, yes those benches, were the nerve center of coolness in Provincetown and bohemian studs and bad girl artists were on every corner. My favorite picture in the book? Beatnik dirty feet in sandals. We all have our twisted memories, don’t we?”

Sokol and Casale decided that the best place to unveil this inaugural project would indeed be Provincetown, in a gallery that featured some of the photographs in an exhibit this summer. “It was amazing,” Sokol says of the opening. “People were like, ‘That’s me!’” Provincetown has become a mecca for artistic types and a gay and lesbian center–the bohemian lifestyle is part of the fabric of the place, no longer the counter culture. “It was gratifying, the reaction we got among that art scene,” says Sokol.

But these photographs that were hanging in the gallery and will be published in the book came at a price, both monetarily and physically.

First off, Sokol and Casale had to find the photos, or what remains of them. “You had to be sort of a journalistic detective,” says Sokol. Kaplan died in 2009 in Miami, but he had begun archiving some of the “tens of thousands of photographs he had taken.” The two tracked down his son and former wife, who turned out to be incredibly helpful, according to Sokol, both in helping with the works but also giving perspective on the man himself.

But then the detailed, tedious and expensive restoration process began. As Sokol writes in the introduction to “There Was Always a Place to Crash,” “digital-era advances in exposure and accessibility have delivered a cruel blow to many talented photographers who began shooting before Instagram and iPhones took hold. Archive-quality analog to digital transfers and restorations remain prohibitively expensive, resulting in work that is trapped on 35 mm film, hidden away in boxes, and largely unknown to today’s audiences.” This is where Casale’s deep knowledge of photography and graphic design made this part of the process possible, says Sokol.

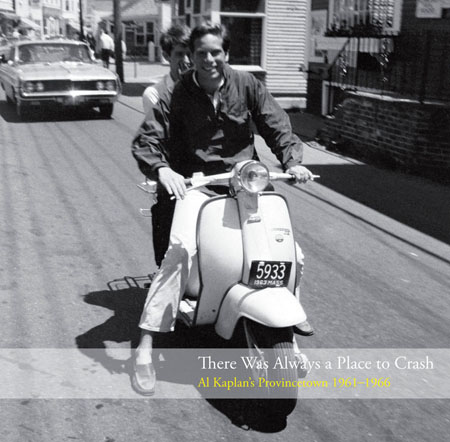

The cover of the debut title from Letter16 press, which will be out in late September.

And here is where Sokol is thankful to the Knight Foundation. No one in the commercial world is going to spend that kind of time and money to restore these golden oldies–there is no real pay back, at least initially. Only “a nonprofit, not concentrating on buzzy young things” would be able to take on the task. “The commitment that Knight has shown us, with a Knight Arts grant, has truly allowed Letter16 Press to happen.”

Happening it is. On the heels of the first book’s publication, the two are readying a second hardcover to be released in time for the Miami Book Fair International in late November. The images this time come from Miami photographer Charles Hashim, who chaired Miami-Dade College’s photography department from 1967-2003. The book focuses again on photographs “during a cusp of massive change,” says Sokol, but the times are of Miami during the early 1980s–“the era that shaped the Miami of today.” After the Mariel boatlift (the 35th commemoration of which is this year), the McDuffie riots, the “Scarface” world of cocaine cowboys, and the re-emergence of Art Deco South Beach, Miami would be transformed, and Hashim’s photographs detail those times. He also, as Sokol notes, found “that sweet spot between photojournalism and art.” An art exhibition at the alternative North Miami gallery Bridge Red will accompany the release through Art Basel.

“Letter16 Press wants to show off this type of quality work,” devoid of the pressures from trends, Sokol says. “It demands to be seen.”

For more information, or to order a copy of the books, visit the Letter16 Press website.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·