‘A Sky the Color of Chaos’: An interview with author M.J. Fièvre

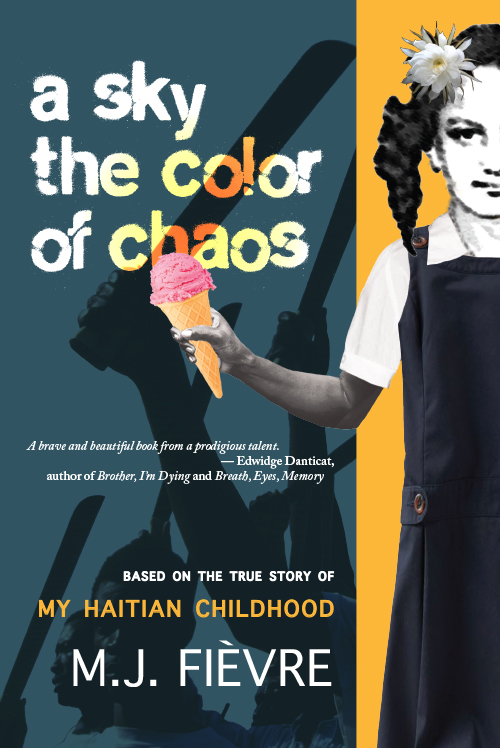

South Florida-based author Michèle-Jessica (M.J.) Fièvre self-published her first novel in Haiti at 16. Since then, she’s published nine books, including a children’s book “I Am Riding.” Her latest title, “A Sky the Color of Chaos,” marks her first memoir. The book is a coming-of-age story that documents Fièvre’s turbulent relationship with her father and his violent mood swings during a time of fierce political upheaval in Haiti.

From the balcony of her childhood home, Fièvre witnessed her first politically motivated killing—a man set on fire in the middle of the street. This would be the beginning of a childhood punctuated by daily violence at home, on the streets, in school and especially after midnight, when thugs loosely aligned with the ‘government’ would terrorize neighborhoods with impunity. Because of, or in spite of, this violence, Fièvre carried a pocketknife on her way to her all-girls Catholic school. From that day on, she became a bit of a bully, eventually stood up to her father–and, well, you’ll have to read the book to find out the rest.

On Jan. 29 at 8 p.m., Miami audiences can experience Fièvre’s work in person. She will be participating in a panel discussion, “Chaos, Dictatorship and Rebirth,” at Knight Arts grantee Books and Books in Coral Gables.

Author M.J. Fièvre.

How has your perspective of Haiti changed since you left, and how much of it never leaves you? In Port-au-Prince, I felt like I was both holding the knife and under it. The striving for control—and fumbling with violence—is a central theme in “A Sky the Color of Chaos.” The violence still inhabits me: I have terrible night sweats, and pain, and suffer from the phantom limb that is my motherland. I still carry the sadness, the shame and the anger of my childhood and young adulthood. The ugliness. The rage.

When I moved to Miami, at first I could only see Haiti with the vindication and unforgiving eyes of a critical stranger with no ties to the island nation. I thought, “Two hundred years of independence and nothing to show for it.” Fraudulent elections. Human right abuses. Gang activities. An incompetent government. It might have been a different cast of characters every so often, but it was always the same story. I was sick of the main strategy used by the corrupted: Bring enough helplessness and hopelessness, and the laissez-faire can go on. Whenever Haiti came up in conversation, not only did I feel pangs of shame, I was also tormented by the unspoken guilt of being part of the diaspora. In order to justify “abandoning” Haiti, I tried to buy into the mainstream media’s narrative of my birth country being nothing more than a (violent) charity case. But if Haiti was such a terrible place, why was it that I was missing her so much? Was I suffering from the transplant’s equivalent to Stockholm syndrome? I became aware of my own disingenuity whenever I didn’t stand against the negative images perpetuated by the media.

In the words of Graham Greene, “Most things disappoint till you look deeper.” The prevalent story of violence, poverty and gore was not the whole story. As a Haitian, I couldn’t experience exile from any other position than that highly embodied, complexly irreducible daughter-of-Haiti position. It was not the same position as that of a foreigner or a “dyaspora” born and raised in the U.S., and that also needs saying, because these nuances of position are subtle and difficult to navigate. I still can’t come to terms with the chaos and corruption in Haiti, but with the distance I’ve grown fonder of the country. I experience what I would call daughterly deference. I often think of Haiti as the mother referred to in the Bible, and whom we should honor. “Anyone who curses their […] mother is to be put to death.” Haiti runs in in my veins. She dictates the way I think and speak and write and move my limbs. She’s in my love of storytelling. She’s in my very breath. Denying my allegiance to her would be spiritual death.

Has this memoir helped you process that period of your life? When I first left Haiti, I was angry. I stopped believing in God for a while, and I stopped believing in Heaven. When I had nightmares, I yelled in French or Haitian Creole, or made deep, animal growls, and my boyfriend would shake me awake. I often could not fall back asleep, wondering what I was doing here, in Miami, alive. I went out for runs. I needed to run, to make treads in the ground. I needed the physical pain, the clenched teeth and clenched fists, in order to deal with all the memories of Haiti—memories that brought me too keenly back to who I had been instead of allowing me to exist as I was. I wanted to hide parts of myself because they were too painful to share. I needed to run all the anger out of me.

And then I’d sit still and write—several languages floating in my head. Stories whose violence was both unapologetic and necessary in their attempt at catharsis.

Writing gives perspective. You look deeper into things. Good writing requires that you reflect on the humanity of individuals, on their fears, their motivations, their mistakes. You think about what they love, about what makes them proud. While writing “A Sky the Color of Chaos,” not only did I acquire a better understanding of my family, I also started seeing Haiti through a writer’s eyes. What could possibly lead to such violence and corruption? As I wrote, I realized how both alive and forgiving stories could feel, and I became less of an expat as Haiti lurked just beyond the reach of the computer screen.

In Chapter Five of “A Sky the Color of Chaos,” you wrote about keeping a list of random deaths in your Hello Kitty diary. What is your relationship with death today? I think about death every day. About my own mortality and the legacy I want to leave behind. I wonder if it’s true that, eventually, we’ll have to answer for our choices in life—for the good, the bad and the unspeakable. I wonder about Paradise. Is it the place described by Haiti’s native “Indians,” a quiet haven where you get to eat apricots for eternity? Or is it that I’ll walk into a white light and meet my grandpa Roger and rekindle my relationship with my father and my grandmothers? Maybe I’ll reincarnate into a cat or an alpaca, or into a yogi meant to continue his/her “learning” on earth. I just hope that, whatever happens after death, I get closure. Loneliness is everywhere—even when I’m not alone. I want to believe that death will remedy this isolation. For now, I keep clawing at life, even when I know it’s no use.

I’m mostly interested, however, in spiritual death. I come from a culture where women are harmed, each and every day, by the dangerous internalized ideas about race, gender and sexuality. I see it in the way Haitian mothers and daughters are treated on the streets, in homes and institutions, and nowadays on social media. These are inherited, paralyzing ideas that I, as a woman, can’t help but carry within me, am forced to live with, and often cost me a fulfilling spiritual/emotional life. Growing up, I internalized patriarchal norms, although I am not without my own understanding of patriarchy. I received mixed messages of independence from both my mother and my papa. I’m constantly engaged in an inner battle, reminding myself that the truth is not limited and defined by the flesh I am born in. I try to silence the little voice inside that claims that a person (particularly a woman) is always and only defined by others, that some external authority is entitled to tell you what you are and force you to conform to that decree. I know a deeper and more complex truth.

“A Sky the Color of Chaos.” All photos courtesy of M.J. Fièvre.

What do you miss most about Haiti? I miss the people and the sense of belonging. In Miami, I’m torn between the Haitian and American cultures, wanting those two ways of life to co-exist without feeling like one has to come out the clear winner. As I’m still working on defining myself, I don’t want it to be a choice between right and wrong, but between right and another right. I don’t want to try grasping for connections that aren’t there.

I also miss how Haiti forces me into philosophical musings. In Port-au-Prince, I live with a looming question: where is the fine line between fighting the good fight and replicating violence?

And I miss my father and how he inspired me to write about what happens when familial authority/ power is expressed in the name of love, protection and well-being.

There’s a scene in Chapter Eight when these spirit chasers are called to cast a spell on these cats that keep meowing at night. But, in fact, it seems like the cats’ cries are the cries of a woman who lives next door. Your parents seem oblivious to the woman. How has the psychological impact of this time on Haiti impact you personally and Haiti culturally? Life in Haiti is hard; it’s not made for the feeble-hearted. Violence and misery are everywhere, and one prevalent coping mechanism involves an ostrich-like approach: if I pretend not to see what’s going on, then it’s not happening. We turn a blind eye to our own role in perpetuating a system that ignores the needs and rights of the majority. In a place where “tomorrow” is so highly hypothetical, it’s each for him/herself. It becomes difficult to sacrifice power and privilege. These truths hurt and overwhelm me. They leave me in a space of deep reflection and meditation, which explains why my stories turn into a barrage of hard-hitting, emotional pieces. Violence has a tendency to show up in a lot of my work. Nevertheless, writing also allows me to pause—to gather up questions and recharge. Take a deep breath. Calm my nerves. I’ve come to realize that it will take an awakening to bring true change to Haiti, and an understanding that only empathy, passion and love can allow us to rekindle our hope and battle on.

Until things change, I don’t know that I will ever move back to Haiti. The idea of Haiti doesn’t terrify me, despite the sheer number of things that could kill you there. I’ve maintained my so-called Haitian resilience, but leaving Haiti changes you, for better and for worse, irreparably. I will continue to write about the country, and I’m certain that the world I write about will continue to be shaped by Haitian politics and history in a very direct way.

What makes you write? Writing nonfiction allows me to rage into the world. To meet what truth the universe has reserved for me by unbending the timeline of my life and gaining insight from stringing one event after the next. I find comfort in words, a cure for the blues. When I write, I believe I grow a little of that inner harmony I keep hearing about. Once I’ve quieted that twinge of hurt and let go of the media-saturated mind, I can hear my inner self—so clearly, so forcefully, with what I can only describe as brutal kindness. Writing takes precedence over the preoccupations of the mind. I enter a stream of consciousness, exploring the influence of past relationships on the present and ways to overcome trauma. Without expectations or demands, I can listen to what a piece of writing is becoming rather than trying to make it be. By the time I’m done with a short story or the chapter of a book, I don’t know if I should cheer or cry. But I know that I can’t help it: I’ll be back to the computer the next day, writing more stories, more chapters. Besides, I’m not really good at anything other than writing and/or teaching it.

Who were your mentors, and how did they shape this memoir? Dan Wakefield and Kim Barnes introduced me to the art of nonfiction. In their workshops, I learned to draw connections between love and violence, either mental or physical, while exploring themes of loneliness, trauma and overcoming. I also learned that our writing costs something of ourselves, and that honesty is always violent, not only to ourselves but too often to those around us. John Dufresne and Vicki Hendricks taught me about careful attention to details. Lynne Barrett taught me about plot. She’s a plot superstar! During the later stages of the writing of “A Sky the Color of Chaos,” I received a lot of feedback and guidance from Edwidge Danticat. She taught me about staying honest in writing about the lived realities of different social spaces in Haiti.

What’s next for you? I’m working on a collaborative project with a Miami-born writer with ties to Chile, and also with an artist of Irish descent. The confluence of all our backgrounds and ideas should be pretty interesting.

For details on other upcoming events in South Florida, visit Fièvre’s website.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·