Models, Braille, philosophy and religion collide at Center for Art in Wood

Through creations both visionary and tangible, two artists give new life to wood in a pair of intellectually stimulating exhibitions at The Center for Art in Wood in Old City. Oversized Braille constructions by David Stephens for the show “Auguries of Idolatry,” and tiny, detailed, Rube Goldberg-type machines as part of “Patent Models For a Good Life” by Roy Superior fill the gallery space with physical forms and imaginative concepts. Each body of work would be noteworthy alone, but together they are all the more impressive.

Roy Superior was, by all accounts, a polymath. Throughout his life he acted as a teacher, artist, writer, musician and food lover – and like his Renaissance inspirations, most notably Leonardo da Vinci, his interest in a wide variety of life’s spices comes across loud and clear in his artwork. Most of what is currently on display at The Center for Art in Wood comes from his unabashedly whimsical series of ‘patent models’ for inventions that not only never were, but could never actually be. This functionless philosophy is sharp-witted and entertaining, as well as beautifully crafted into detailed models.

An exemplary testament to Superior’s style is the “Peace Missile.” Delicately crafted from multiple types of hardwood, brass and a music box, the container lies open with its ballistic contents rising up from within. Part nuclear warhead, part birdcage, this rocket contains no explosives, but simply a pair of white doves. The expectations of war and violence are stricken down with acerbic effect, substituting humor for atrocity and a peaceable kingdom for an arms race.

Roy Superior, “The Human Condition.”

In “The Human Condition,” a slightly more sobering contraption proves with lighthearted adroitness that despite our best efforts, the burdens of life often stop us from achieving everything we desire. A tall, unwieldy tower with underdeveloped wings seems expertly assembled, even if its vestigial wings will never allow it to leave the ground. If that weren’t enough, a hunk of stone labeled “Real Life” lies chained to its underbelly. Instead of presenting reality with dismal undertones, Superior turns the tables on hardship by making light of these setbacks instead of allowing them to best him.

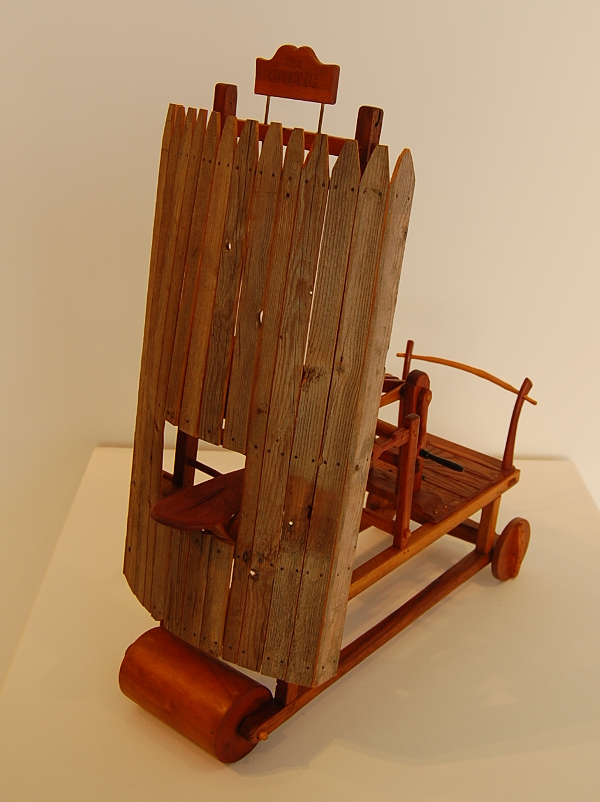

Roy Superior, “The Critic.”

Utilizing a similar irreverence in the face of adversity, a little vehicle entitled “The Critic” is fitted with a flattening steamroller front and a shield instead of a windshield. Rendering the driver unaware of the road ahead, a set of wooden teeth and tongue alternately chomp and stick out of a cutout hole in the center, simultaneously running down and mocking all in its path.

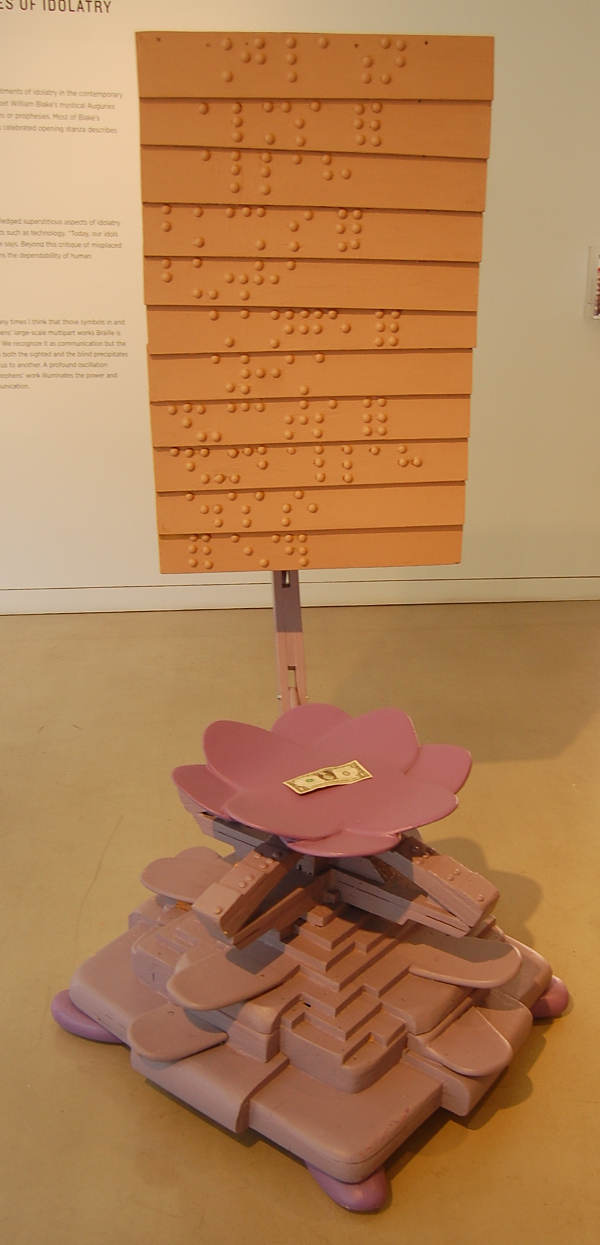

David Stephens provides a tactile take on wooden sculpture that spans both the auguries (prophecies of divinations) of William Blake’s poetry, as well as the likenesses of religious idols and the more modern power of language in the form of Braille. As a working artist, Stephens lost his sight over a period of years, but continued making art, including the tall, layered structures found here.

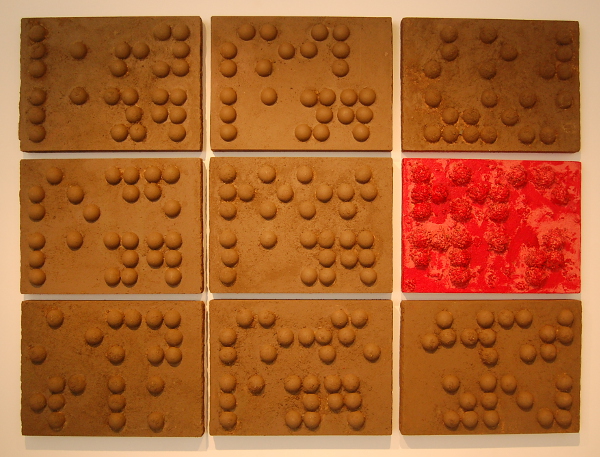

David Stephens, “Peeled Turf.”

The piece “Peeled Turf” provides a fractured poem in the form of nine rectangular wall-mounted tiles depicting two-word phrases. All of them are gray and textured save one, which is a rosy red and made with the actual botanical elements of firmly curled rosebuds. This linguistic study is tied to Stephens’ plan to introduce Braille into landscape or garden settings.

David Stephens, “Cenotaph: TOBB (Tower of Brothers’ Blood).”

Elsewhere the monumental works by Stephens are just that – memorials meant to mimic gravestones or monuments. They are inscribed (in Braille) with the names of those who died by their own hands, at the hands of others, due to their habits, or the habits of others, and seek to recall the lives of those who were close to the artist. They are also openly seeking ‘alms for Allah, change for Christ,” as their flat surfaces rest open for donations that double as blessings or wishes.

David Stephens, “Gethsemane Gate.”

Acting as a sort of centerpiece to the exhibit is “Gethsemane Gate,” which draws on allusions to the legendary cemetery where Jesus prayed before his arrest. Two columns stand tall aside four panels containing text, arranged in the form of a cross. The words and images here are steeped in Biblical imagery and seem to invite the viewer in toward the central cross. This entryway to spiritualism beckons, but it also presents the dilemma of transcendence in an all too physical world. Seemingly a safe place for contemplation, the gate’s text is emblazoned with the three-inch Braille bumps found throughout the show. Paired with a text by William Blake, this combination of Biblical and poetic words offers introspection through visually read and physically touched manifestations of language. Stephens unfurls a mythology that borrows from many places but remains steadfastly his own.

Both shows will be on display at The Center for Art in Wood through April 19.

The Center for Art in Wood is located at 141 North 3rd St., Philadelphia; 215-923-8000; centerforartinwood.org.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·