Election Perceptions 2, a hunch: Does a major new form of rising media always encourage presidential voting?

Today’s post is the second of three looking at the media and elections. It is a wild hunch that our great political scientists will not agree with – still, I think it needs study from journalism and mass communications scholars.

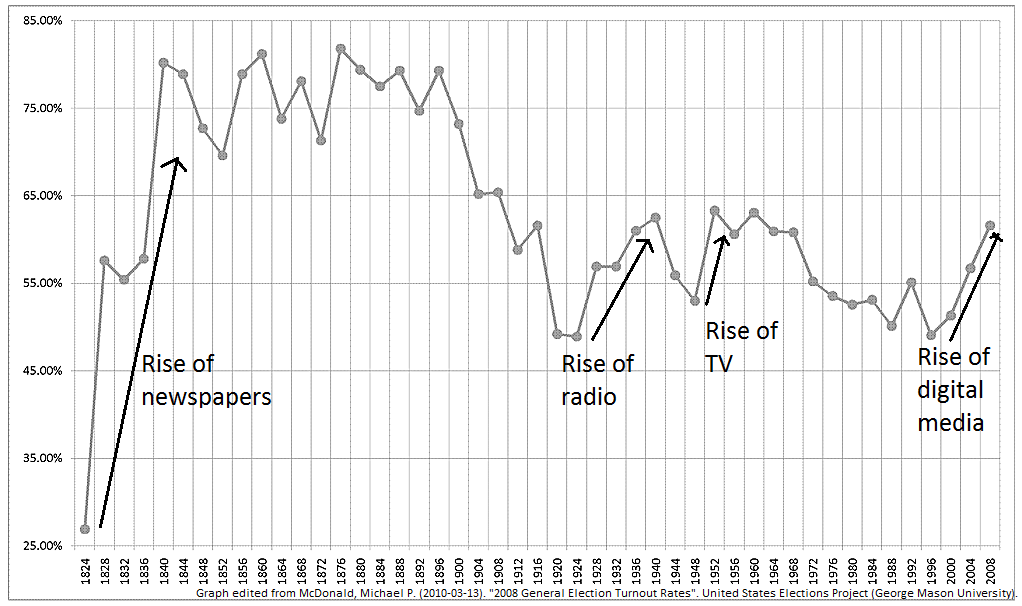

Take a look at the graphic. From George Mason University, via Wikipedia, it shows presidential election turnout in the United States for the past two centuries.

There are four interesting upward spikes in U.S. election turnout: 1820s-1850s, which just so happens to coincide with the rise of the mass circulation newspaper; 1920s-1940s; which matches the rise of radio; 1950s-1960s, during the time of the rise of television, and from the mid-1990s to today, which coincides with the rise of the World Wide Web and digital media.

Drawing upon my years co-creating the Newseum, the international news and freedom museum in Washington, D.C., I would also throw in a couple of 19th century mini-spikes. After American magazines rose just before the Civil War and after the rise of big city papers before the turn of the century, there were also presidential voting spikes.

So I repeat: The historic upticks in American presidential voting happen to match the rise of new forms of mass media.

Is this just a coincidence? I don’t think so. But don’t get me wrong. I am NOT saying that the rise of novel forms of popular media caused the spikes. I am theorizing that the rise of media is an ingredient in a complex recipe that in the end results in more presidential voting. In fact, the same underlying social conditions that caused the rise of the new forms of media might also be the things that caused the rise of presidential voting.

Pulitzer Prize-winning Princeton scholar Paul Starr, in his book The Creation of the Media argues that there was a relationship between political activity and newspapers in the early 19th century. The first mass political parties inspired “party newspapers,” and that accelerated the penny press, making newspapers cheap for all, which accelerated party activity, and so on.

A strong newspaper connection sounds right to me. Alexis de Tocqueville, the French political thinker who studied America in the early 19th century, seemed certain when he wrote “if there were no newspapers there would be no common activity.” And our great poet Walt Whitman said “America is a newspaper-ruled nation.” Abraham Lincoln, as a young postmaster, read the newspapers from everywhere and used them to master America’s emerging democratic language, creating a speaking style that interested people from all over a sprawling country.

Let’s jump to the second spike, from the 1920s to the 1940s, during the rise of radio. Many scholars would say that this is simply the increase in the number of women who had gotten the vote in 1920. Others would say it is because of the big issues that were being decided, such as the New Deal. Others might say President Roosevelt’s radio-broadcast fireside chats played a role. What if it was all these things? A new group of voters, exposed to the big issues and president’s messages in the home via radio news?

Here are some notions of why the rise of a new form of major mass media might always be an ingredient in presidential voter spikes: 1. Because the emerging medium is new, a lot of Americans pay attention to this novel innovation; 2. Since it carries news, the pool of people aware of that news increases; 3. They then talk a lot about it, and 4. The people who have engaged in news and debate then go on to engage in public life, at least at this high, measurable level, by voting for president.

Can I prove any of this? Not a word. That’s why I call it a hunch. Certainly there is validity to those that say news alone doesn’t actually do anything. People must have the capacity and ability to act on it. Even so, isn’t this pattern just too odd a coincidence to be a total coincidence?

Sociologist Michael Schudson, whom I trust a great deal, tells me there has been some significant scholarship linking the rise of TV and of the web to the kind of greater political interest we’re talking about, but that its still in the realm of theory, not at all proven.

Because we are experiencing the fourth big spike right now – the rising of presidential voting and the emergence of digital media – it seems a good time for even more study. It’s important because young people are big both in digital media and in new presidential voting. If the voter turnout actually increases in 2012, a lot of experts will be shocked. Even if it doesn’t, an increase in youth voting might still support this hypothesis.

Could digital media, which seems to be forever new, drive political interest beyond 20th century levels back up into the high ranges of engagement that existed when only certain white men could vote? If the crazy, politicized blogosphere is like the old party newspapers, is that causing increasing voting? The Knight Commission on the Information Needs of Communities agreed that without broadband media, you’re a second-class citizen – so can we agree that with it, you’re more prone to first-class engagement?

One way to study this might be to find two parts of America that are alike in as many ways as possible except broadband penetration, and then compare turnout in the election.

The hunch that emerging mass media forms, when they are new and on the rise, really could make a big difference came out of a talk I gave at Arizona State University, showing that every American generation has grown up with a different form of media on the rise. My hope was that this talk would help today’s journalism students understand that the ever-changing new technologies are nothing new, so they should seize the day and relax into the information delivery worlds like this one.

By Eric Newton, senior adviser to the President at Knight Foundation

Recent Content

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·