Let’s talk about free speech

What is the state of the First Amendment on college campuses? In the past year, this question has been one of significant interest to Knight Foundation, and to observers around the country. As a private foundation with its roots in the newspaper business, we have a longstanding commitment to the First Amendment.

For this reason, we took note last fall when protests on college campuses over myriad issues spurred a surprising paradox: Protesters – exercising their right to free speech – simultaneously seemed to limit the speech of others through the creation of “safe spaces.” This trend came to a head most dramatically at the University of Missouri last October, when students briefly attempted to ban the press from covering their protest in a public space, before quickly recanting and permitting press access.

These are complicated issues, in many cases bringing together tense debates about race and diversity in institutions of higher education as well as longstanding beliefs about the nature and purpose of liberal education. But that, of course, has always been the crucible of the First Amendment; it is the place in our Constitution that forces us to ask what we want our speech, our beliefs and our public space to look like, and often brings us into direct contact with ideas that blur the lines of civility, decency and comity.

Given these complexities, we believed our first responsibility was to improve the information available. We sought to gain a better understanding of how higher education students are actually thinking about these issues. The result is a major survey of university students from across the country.

Related Links

“Historically Black College and University Students’ Views of Free Expression on Campus,” Knight Foundation, Gallup 9/22/2016

“Students at historically black colleges and universities more likely to favor limits on press’ right to cover campus protests, express less trust in media, Gallup survey shows” – press release, 9/22/2016

Our approach was expansive: We spoke to over 3,000 randomly selected college students, as well as 302 students who attend historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs). A subset of the survey was administered to over 2,000 adults, including an oversample of 250 Muslim adults. We believed it was important to hear from such diverse groups because we hypothesized that issues of background and identity play a role in shaping preferences and views on free expression.

What we found was a portrait as complicated as what we imagined, although not in the ways we expected. Among the key findings:

- Disagreement on the security of First Amendment freedoms: While U.S. adults and college students both agree that most of the five freedoms in the First Amendment secure, college students are more sanguine, particularly with regard to freedom of speech (56 percent among U.S. adults versus 73 percent among college students), freedom of the press (64 percent versus 81 percent) and freedom to petition the government (58 percent versus 76 percent). Race, however, is a significant factor: Non-Hispanic black college students (39 percent) and students at HBCUs (45 percent) are much less likely than non-Hispanic white college students (70 percent) to believe the right of people to assemble peacefully is secure.

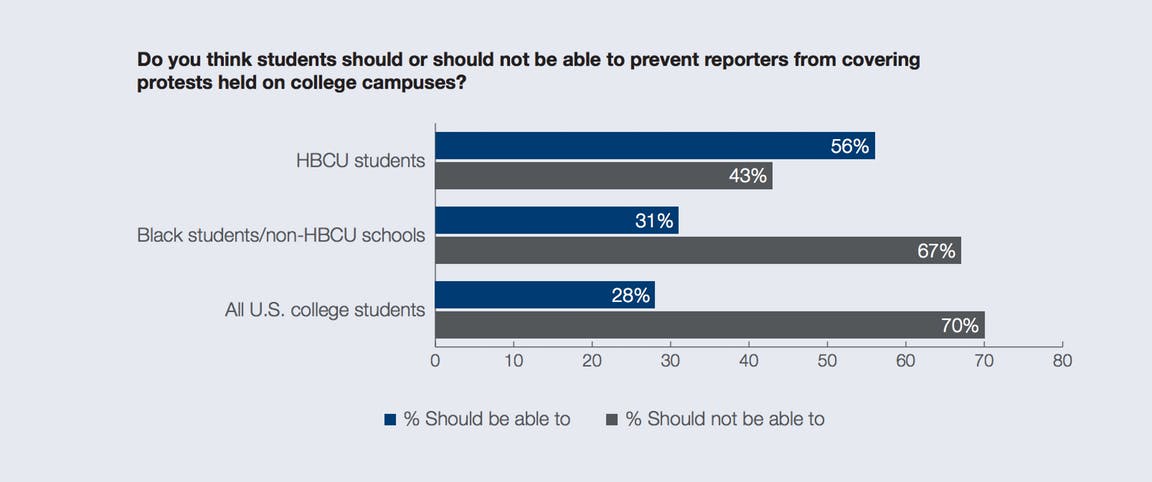

- Principles and practice don’t match up: When it comes to the principles undergirding the First Amendment, college students are generally more ardent than U.S. adults that colleges should expose students to all types of expression and points of view rather than prohibiting biased or offensive speech (78 percent among college students versus 66 percent among U.S. adults). In addition, a strong majority of college students (70 percent) say reporters shouldn’t be prevented from reporting on a protest. But when it comes to specific restrictions on freedom of expression and the First Amendment, college students are divided: Sizeable minorities say protesters can bar media because they have a right to be left alone (48 percent), because the protesters want to tell their own story (44 percent), or because they believe the press will be unfair (49 percent). HBCU students are even more willing to consider such restrictions. A majority (56 percent) believe that students should be able to bar reporters from covering campus protests. Similarly, majorities endorse potential reasons for preventing reporters from covering protests: because protesters have a right to be left alone (73 percent), because the protesters want to tell their own story (62 percent), or because they believe the press will be unfair (73 percent).

- Social media seen as positive and negative force for expression: At colleges and universities, significant expression and speech is happening online, particularly through social media tools and platforms. College students are nearly unanimous in the empowering aspects of this: that it allows people to express their views (88 percent) and have more control over their story (86 percent). But there is ambivalence, too: that social media too easily permits anonymity (74 percent) and that it stifles free expression through shaming and attacking (49 percent—a narrow minority). Overall, a majority of 60 percent do not agree that the dialogue on social media is civil. Despite mixed feelings regarding social media as a form of communication, when it comes to finding news, college students still favor traditional news sources over social media by a margin of 51 percent to 26 percent.

This is just a sample of what we learned. The full reports and datasets for these studies can be found here.

What has largely been absent from the seeming collision between the principles of the First Amendment and emerging patterns of expression and activism on campus are data. These studies seek to fill that void by providing some of the most comprehensive data to date about what college students from different backgrounds, campuses and views think about these issues. At a time of significant flux in attitudes and beliefs, particularly among the rising generation, we believe this is an important contribution.

Sam Gill is vice president for learning and impact at Knight Foundation. Email him at [email protected] and follow him on Twitter @thesamgill.

-

Journalism / Article

-

Journalism / Article

-

Journalism / Article

Recent Content

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·