Looking across languages: Seeing the world through mass translation of local news

Below, Kalev H. Leetaru, a data scientist and the past 2013-2014 Yahoo Fellow at Georgetown University, writes about the future of mass translation of the world’s news media.

Imagine a world without language barriers, where journalists and citizens can access real-time information from anywhere in the world in any language, seamlessly translated into their native tongue and where the articles they write are equally accessible to speakers of all the world’s languages. Authors from Douglas Adams to Ethan Zuckerman have long articulated such visions of a post-lingual society in which mass translation eliminates barriers to information access and communication. Yet, even as technologies like the Web break down geographic barriers and make it possible to hear from anywhere in the world, linguistic barriers mean most of those voices remain steadfastly inaccessible.

There have been many attempts to bridge the language divide. During the 2013 Egyptian uprising, Twitter launched live machine translation of Arabic-language tweets from select political leaders and news outlets, an experiment which it expanded for the World Cup in 2014 and made permanent this past January with its official “Tweet translation” service. Facebook launched its own machine translation service in 2011, while Wikipedia’s Content Translation program combines machine translation with human correction in its quest to translate Wikipedia into every language. TED’s Open Translation Project has brought together 20,000 volunteers to translate 70,000 speeches into 107 languages since 2009. Even the humanitarian space now routinely leverages volunteer networks to mass translate aid requests during disasters, while mobile games increasingly combine machine and human translation to create fully multilingual chat environments.

Yet, these efforts have substantial limitations. Twitter and Facebook’s on-demand model translates content only as it is requested, while Wikipedia and TED’s volunteer workflows impose long delays before material becomes available. Journalism itself has experimented only haltingly with large-scale translation. Notable successes such as Project Lingua, Yeeyan.org and Meedan.org focus on translating news coverage for citizen consumption, while journalist-directed efforts such as Andy Carvin’s crowd-sourced translations are still largely regarded as novelties. Even the U.S. government’s foreign press monitoring agency draws nearly half its material from English-language outlets to minimize translation costs, while the earliest warnings of the Ebola outbreak were missed because they were in French.

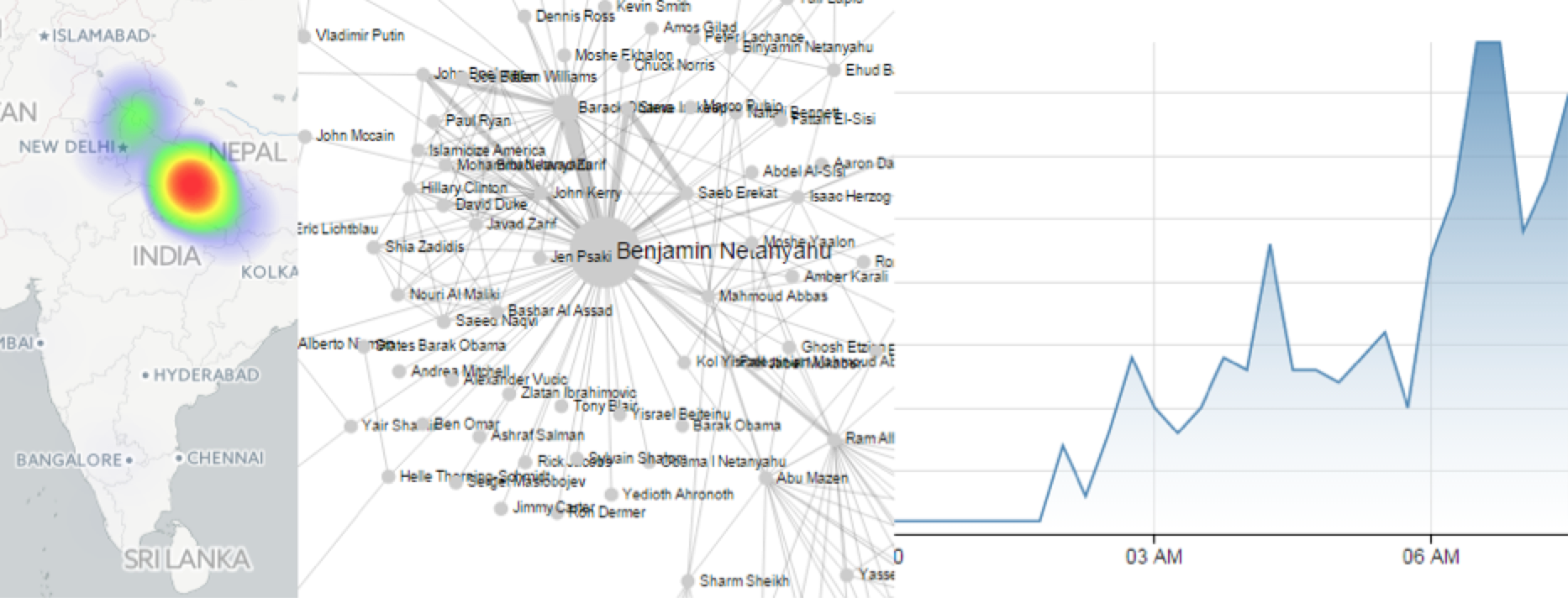

What would it look like if one simply translated the entirety of the world’s news coverage each day in real-time using massive machine translation? For the past two years the GDELT Project has been monitoring global news media, identifying the people, locations, counts, themes, emotions, narratives, events and patterns driving global society. Working closely with governments, media organizations, think tanks, academics, NGO’s, and ordinary citizens, GDELT has been steadily building a high resolution catalog of the world’s local media, much of which is in a language other than English.

Enabling GDELT to look across this material holistically required construction of a massive machine translation infrastructure capable of real-time translation of the world’s daily journalistic output in 65 languages. The translations themselves are not made available to the public, but are instead used to apply a range of computer algorithms to tag and extract key pieces of information about each article’s events, emotions and narratives, creating a multilingual catalog over the world’s news. GDELT Live brings this data together into a real-time global news dashboard, allowing a search for a major person, organization, location or topic to transparently reach across the world’s local news in 65 languages. A search for “Yemen, bomb” in the hours after the March 20, 2015 attack yielded reaction and emerging details from across the world, giving journalists and ordinary citizens a global perspective on local events.

Finally, the increasing fragility and ephemerality of journalism in many parts of the world means that language barriers are not the only obstacle to accessing local events and perspectives. Local coverage is increasingly disappearing at the pen stroke of an offended government, at gunpoint by masked militiamen, by regretful combatants or even through anonymized computer attacks. In perhaps the single largest program to preserve the online journalism of the non-Western world, each night GDELT sends a complete list of the URLs of all electronic news coverage it monitors to the Internet Archive under its “No More 404” program, where they join the archive’s permanent index of more than 400 billion Web pages.

We have finally reached a technological junction where automated tools and human volunteers are able to take the first – imperfect – steps towards mass translation of the world’s information at ever-greater scales and speeds. Just as the Internet reduced geographic boundaries in accessing the world’s information, one can only imagine the possibilities of a world in which a single search can reach across all of the world’s information in all the world’s languages in real time.

Recent Content

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·