Making poetry from the pain of war

As readers, listeners, viewers or creators, we often turn to art to transmute pain into beauty, to find clarity in our darkness, to explain ourselves. Sometimes a work of art might start with a simple need. For a veteran, it might be an answer to a silent question: how do you tell your neighbor what it was like to live with unspeakable violence, fear and death, in an unknowable place, half way around the world? Or, how do you tell it to yourself?

Those questions are at the heart of Live Arts Veterans’ Lab Showcase: “Conscience Under Fire,” a spoken word performance presented by MDC Live Arts at the Betsy Hotel, Miami Beach, on April 19, as part of the O, Miami Poetry Festival.

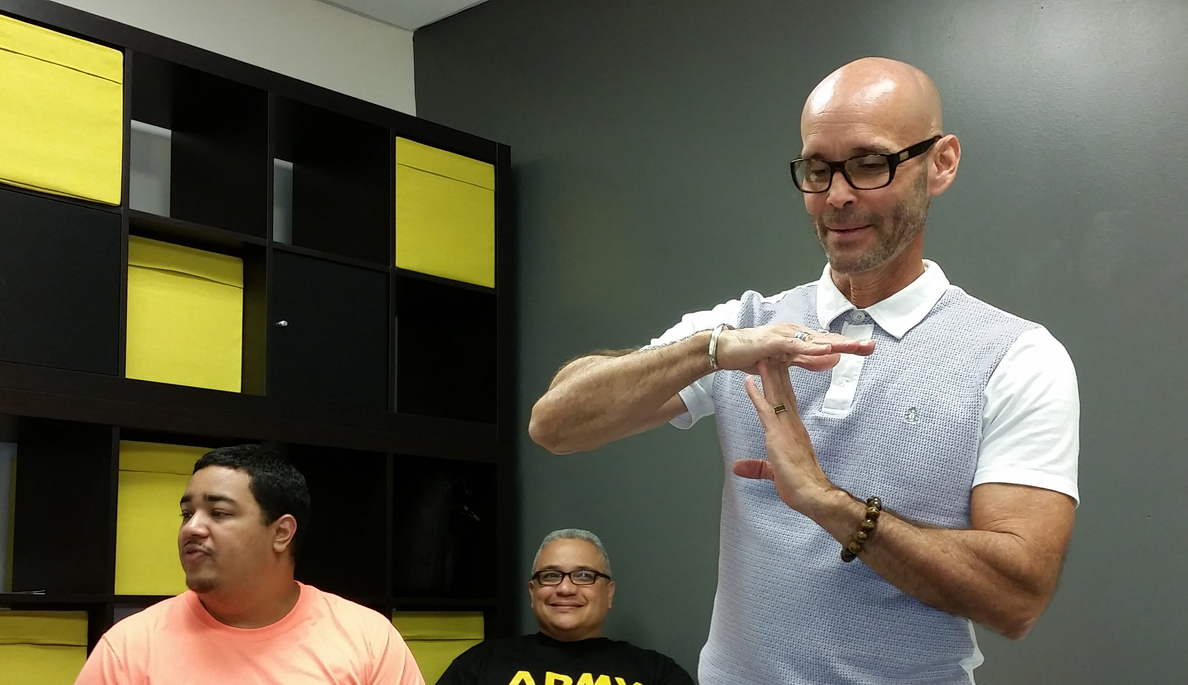

Loosely structured in three parts — childhood, service and post-service life — the event is the culmination of The Live Arts Veterans’ Lab, a creative writing and storytelling workshop led by Knight Challenge winner, actor, writer and director Teo Castellanos. The event is part of an MDC Live Arts’ challenge-winning initiative focused on veterans.

“In the military, you are part of a cohesive unit, you are part of a family, then you come home and you have your relatives, your ‘other’ family, your other friends. But there is never the kind of bonding that you get in the military,” said Anthony Torres, a mental health specialist, who served at the hospital in the infamous Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. Torres was part of a unit that provided medical and mental health to both the troops in that area and the detainees. “A lot of us miss that [bond] and some of us seek it in the civilian world. This project gave us a platform to come together with a common goal and a purpose.”

Torres, who was in active duty from 2002 to the summer of 2006, is attending Barry University, studying for a master’s degree in social service. He was instrumental in engaging fellow veterans Andrew Cuthbert, Hipólito Arriaga and Allen Minor, who is also his cousin, in the writing workshop.

“There is definitely a therapeutic aspect to the project,” said Minor, who served at Mortuary Affairs, in Maryland, from 2006-08. Mortuary Affairs is a service within the United States Army Quartermaster Corps. that takes care of the remains and personal effects of soldiers who have died overseas. “We receive them, perform the autopsies, get them ready for the funeral service and send the remains to their families,” explains Minor. “ [From overseas] they also will send us all the personal effects they would have on and with them when they died.”

The military experience “it’s not really something you can talk about with a person in the civilian world and have them relate, “ Minor said. “Writing it out, even if you are not necessarily writing about your own experience, gives you an opportunity to put down your true, honest feelings on paper.”

That in itself can be life-changing, said Minor, “because after getting out of the military you get in the habit of keeping everything inside because you start to feel that no one would understand anything you’d say anyway.”

But writing it out doesn’t come easy.

Andrew Cuthbert is a Marine who saw combat in Iraq (2005-2006), and also served two posts in Africa and in Beijing, China and then served another year in the reserves.

Cuthbert started writing when he was in the eighth grade. He writes “all kind of things, but I really focus on poetry,” he said. But, while deployed, he didn’t write because he “would try and get too angry, and I didn’t want to get in contact with my emotions like that.”

“It took me awhile to get going again because when you go to war you can’t be too emotional. If one of your friends gets hurt or killed, you can’t cry about it. You can’t react. So you get into the habit of suppressing your emotions. You learn to not do anything with them — until I found out how bad it was affecting me. I call it ‘poison in a jar’ except that the jar is not made out of glass … and the poison is always seeping through. That’s how I felt until I finally said ‘I need to get this out of me,’ and I started writing again.”

For Hipólito Arriaga, a Marine who served from 2003-07 and was twice deployed to Iraq, the writing lab has been “a journey of self-discovery.”

Arriaga speaks of “being really into writing” as a young man and then “kind of losing contact” with it as he got older — only to get it back after completing his service, on a veterans’ white water raft outing in Utah, where he was encouraged to keep a journal.

“It’s been hard to express some of my experiences [as a Marine] openly,” he said. “It’s a very difficult conversation — just to start . Taking part of this creative process has allowed me to let these things come out freely in a way I haven’t been able to do before. It’s been very cathartic, very therapeutic.”

A key element in this process, and a common theme mentioned by all of them, is having fellow veterans in the group who not only can relate to their experiences but also understand the emotional and psychological cost of them. In the dynamic of the group, Castellanos has not only played the role of guide and director but, as the one non-veteran in the group, he has also served as a stand-in for those in the audience who have not had combat or service experience.

“It helps to be with people who have shared experiences,” said Arriaga. “You don’t have to explain to them the nuances. They know. And that definitely alleviates some of the confusion. But also working with Teo, who doesn’t have any military experience, while it was a challenge, it also showed me that it was something that needs to be done.

“The majority of people don’t have military experience. We need to communicate with them. We have to learn how to bridge that gap. Hopefully, this is a way I can learn to do that.”

Fernando González is a Miami-based arts and culture writer.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·