In Kenya, a group of technologists had a vision: use citizens texting on cell phones to help map post-election violence. Today, their Ushahidi crowd-sourcing platform operates in 132 countries. People have used it to map crime in Panama, track the Gulf of Mexico oil spill, even help rescue efforts after the earthquake in Haiti.

In Macon, Georgia, a professor afraid to walk her dog at night had a bright idea: get neighbors to keep their porch lights on. Today, porches in her College Hill neighborhood use fluorescent bulbs with photo cells that turn on at dusk. Residents can walk the well-lit streets with confidence.

In Miami, a lone drummer had a brainstorm: to bring the world of rhythm and percussion to local youth who had little or no knowledge of music. Today, the troupe of drummers draws sold-out concert crowds.

Large visions. Bright ambitions. Homespun dreams. What do they have in common? Each was a project the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation never would have supported were it not for contests.

Since 2007, Knight Foundation has run or funded nearly a dozen open contests, many over multiple years, choosing some 400 winners from almost 25,000 entries, and granting more than $75 million to individuals, businesses, schools and nonprofits. The winners believe, as we do, that democracy thrives when people and communities are informed and engaged. The contests reflect the full diversity of our program areas: journalism and media innovation, engaging communities and fostering the arts. Over the past seven years, we have learned a lot about how good contests work, what they can do, and what the challenges are. Though contests represent less than 20 percent of our grant-making, they have improved our traditional programs in myriad ways.

A 2009 McKinsey & Company Report, “And the winner is..., ” put it this way: “Every leading philanthropist should consider the opportunity to use prizes to help achieve their mission, and to accept the challenge of fully exploiting this powerful tool. ” But of America ‘s more than 76,000 grant-making foundations, only a handful, maybe 100 at most, have embraced the use of contests. That means 99.9 percent do not.

Sharing these lessons here is an invitation to others to consider how contests, when appropriate, might widen their networks, deepen the work they already do, and broaden their definition of philanthropic giving.

Before you launch and manage your own contests, you might want to consider the six major lessons we ‘ve learned about how contests improved our philanthropy.

A key part of a foundation’s role is looking for new people and good ideas: but how? Contests open up unique avenues for meeting people you would otherwise not know. This, in turn, expands and refreshes the networks working on the causes a foundation cares about.

In our journalism work, for example, our traditional grantees had been blue-chip journalism educators and top-notch newsrooms. Yet the digital age turned communications on its head. So we used the contest as a means of disrupting and enriching that traditional network by attracting new people from new disciplines. The Knight news challenge— our first competition, launched in 2007 — put us at the hub of an energetic community of media innovators, including software engineers, designers and entrepreneurs.

A case in point: In New York, three tech-savvy journalists had a dream of creating a place in the cloud where primary source documents could be stored, annotated and read. Today, their free, open-source document cloud hosts more than 5.5 million pages. Reporters used it to expose the hijacking of millions of dollars in public money by the now-deposed city leaders of Bell, California. As with many others, this new digital tool, now used by hundreds of newsrooms, was not created by journalists alone. They needed the help of open-source data software jockeys.

We still partner with organizations like columbia university’s graduate School of Journalism, but its digital media research is now informed by a winner of the news challenge, the mit media lab, where engineering students are designing and deploying new civic media tools and practices.

Tapping the wisdom of the crowd with a contest means opening a foundation up to new kinds of applicants. The Knight arts challenge exposed Knight Foundation to a host of new talent and creativity. For example, nearly half of the contest entries in the first four years were, surprisingly, not 501c(3) nonprofits. They were individual artists (30 percent), even businesses (10 percent). Many said they would not have applied for a traditional grant because they didn’t think they would be welcome. The openness and simplicity of the contest format changed that.

A case in point: Miami artist-writer Gean Moreno said he never would have applied for a traditional grant. But through the arts challenge, he launched a not-for-profit press (Miami’s first) to give local artists an outlet for showcasing their ideas. Similarly, in our Macon, Ga., Knight neighborhood challenge, roughly 25 percent of the entrants surveyed indicated they had never before applied for regular foundation grants.

Keep the entry process simple so people not schooled in how foundations work can apply.

In our arts challenge, we ask for only an initial 150 word description of the project on a simple form on the web. As finalists advance, we ask for a short formal proposal with a few questions and a budget.

Invest in marketing to help you reach out widely to your target community.

In the Miami Arts Challenge, we marketed the contest and accepted applications in multiple languages (English, Spanish and Haitian Creole). In the News Challenge, we looked for partners to help us reach sub-communities where we initially didn’t have strong contacts, such as Bay Area entrepreneurs, software developers and startups.

Remember that when it comes to innovation, faster is better.

In the early years of the news challenge, there was an eight-month cycle between the receipt of entries and the announcement of winners. We learned that this lag was inconsistent with the rapid pace of innovation in media. In 2012 we reduced the cycle to 14 weeks to help applicants better respond to market opportunities.

DDepending upon the competition, the odds of winning one of Knight’s contests are, at their lowest, one in six, and at their highest, more than one in 100. But if you think of your contest only as a funnel spitting out a handful of winning ideas, you overlook what’s really happening. A good contest is more a megaphone for a cause.

We started the arts challenge to find new ways to build on the momentum of an already thriving creative community in Miami. In that competition, more than 40 percent of the non-winning entrants surveyed said just the process of applying was beneficial. Often, just putting the ideas down in writing helped refine them. At the same time, the contest helped applicants find new partners. They got more organized. Half said they were still pursuing their ideas in some way despite not receiving funding.

To get the best “halo effect”, you need to build a contest’s imprimatur, so people associated with the brand benefit whether they win or not.

Promote contest finalists.

In many of our contests, we profile finalists on our website. We blog and tweet about them. This brings a meaningful bump in credibility and attention for these applicants. (Finalists often tout their status on their organizational websites and personal resumes.)

Think of marketing as more than just a way to attract new entrants.

It is a way to build a brand whose cachet spills over to all involved, not just those who win.

Include other funders in your reviewer pool.

You can share contest knowledge with them. They may fund ideas you don‘t.

Though both approaches have merit, our contests are generally based on broad topic areas rather than on solving a very narrow question or problem. In our Arts Challenge, for example, we require only three rules: that the entries are about the arts; the project takes place in the community where the challenge is based; and that they come up with matching funding from the community. When you receive more than a thousand applications from a community in an open contest, you can get a good sense of what people are thinking about, what’s going on beneath the surface.

In Miami, a review of the arts contest applicants confirmed some things we already knew. The city is strong in visual arts. But when we looked closer, we saw a growing performance dance scene, independent filmmaking and live music in corners we wouldn’t have suspected. We are now watching those trends in our regular arts program. As one of our grantees, Sweat Records, said: “The underground doesn’t stay underground forever.”

Our news challenge applicant pool has helped us identify trends in the news community. We were early in funding emerging trends like data journalism and mobile apps. In the early years of the contest we noticed a number of new digital nonprofits trying to fill the void left by shrinking local newspapers. We ended up taking a closer look at this trend, and supported various fledgling digital journalism groups such as the MinnPost and the Voice of San Diego, through our regular journalism grant programs. If we had looked only at the Knight News Challenge finalists, we would have missed this issue.

Make it one of your judging panel‘s jobs to identify patterns

in the applicant pool.

What surprised them about the entrants? Are there any issues they think the foundation should be paying attention to?

Look for trends in the entries at large as well as in the finalists.

When you‘re running an open contest, your applicant pool generates a lot of useful data that should be mined. It tells you who you‘re reaching? What their concerns are? What organizations they hope to partner with?

Treat your applicants as problem identifiers not just solution providers.

Even entries that don‘t offer a feasible project idea worth funding still provide you with potentially useful feedback on the issues they think need fixing.

Contests are almost certain to cause you to change entrenched foundation behaviors. This may sound internally focused, but it isn’t. If your traditional funding changes, that’s a bigger pot of money than the contest pool. Before contests, we rarely funded individuals directly. Most of our funding had gone to nonprofits or established institutions. In the first two years of our news challenge alone, we funded 14 individuals. The excitement of seeing good ideas from individuals, as well as from businesses, caused us to set up new ways to fund them. As a result of the contests, we began to make different types of grants, taking on expenditure responsibility grants, and we now serve individuals and for-profit startups as part of our regular grant-making work. As a result of our contest work, we also shortened application forms for all grants and changed our due diligence requests. We found the shorter contest forms were giving us all we really needed. We also moved some applicants out of contests when they weren’t the right fit, funding them instead in our traditional program areas. And we’ve given contest winners follow-up funding outside of the contest. We’ve rearranged staff so that we can manage external reviewers and an aggressive marketing campaign. Finally, contests help create a “safe zone” for risk-taking and experimentation in a foundation — supporting new ideas and trying out creative ways of funding that, if successful, might spill over into your regular grant-making practices.

Embrace a contest‘s signaling effect.

The marketing and outreach that goes into a contest make it a powerful mechanism to broadcast changes in a foundation‘s approach and focus.

Experiment with an open brand.

A contest‘s effectiveness often derives from its accessibility and ability to use the web and social media effectively to draw in diverse groups and unusual ideas. Contests offer foundations an opportunity to rethink the openness of their grantmaking practices and how they respond and interact with what people share and post online about the contest and its applicants.

Review your contests frequently.

By monitoring what works well in a contest and what doesn‘t, you can see how you might layer some of the most successful innovations and approaches into your traditional program.

with existing program strategies

FFoundations shouldn’t undertake a contest as a lark or a just-for-the-heck-of-it enterprise. The most successful are embedded in existing program strategies. They are simply a different way to tackle a foundation’s key areas of focus.

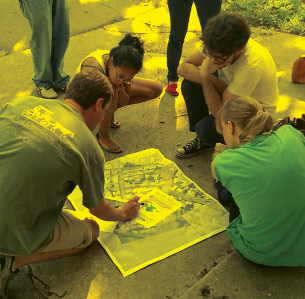

In Macon, Ga., for example, Knight has funded major projects to revitalize the college hill corridor, the historic and downtown districts seen as keys to citywide renewal. In tandem with those projects, we started the Macon Knight neighborhood challenge, a five-year, $3 million contest inviting residents to submit novel ideas for improving life in their neighborhood. We focused the challenge around residents’ own ideas for making College Hill a clean, safe and thriving place — issues they had identified at an initial community planning meeting for the revitalization project. We received a host of improvements that otherwise may not have seen the light of day. Projects, most under $15,000, include restorations and small graffiti clean-ups, a community garden and composting workshop, even local music festivals. These modest projects are all taking place in and around the larger community renewal effort, enhancing local development with creative input from residents.

On their own, contests are not the answer. But if tactically linked to existing program strategies they can deepen a foundation’s core mission in surprising ways.

Piggyback where appropriate on community priorities.

Building on the issues that individuals themselves have expressed an interest in or need for broadens the appeal of a contest and strengthens potential participation.

Identify market areas within your portfolio that have stalled.

Contests can be a useful way to kick start action and garner attention for specific issues.

Spotlight leading practices.

While the application period is open, highlight exemplar ideas or valuable practices to help motivate and influence potential entrants.

engage the community

To get the most out of competitions, you need new judging systems. If a foundation puts new ideas through the old selection mill, nothing really new will emerge. But if people in the community can comment on or even help choose the winners, they feel engaged, which further promotes the contest. But tapping into the wisdom of the crowd can be a tricky proposition. You must guard against lesser ideas winning just because they come from the most popular sources.

In the Knight news challenge, all applicants are strongly encouraged to post their entries on the web. Anyone can post a remark. This provides valuable feedback to the applicants, even if they don’t win. More importantly, the open system makes everyone feel welcome. In 2013, we took community participation a step further. We partnered with design firm IDEO and used their open innovation platform for crowdsourcing ideas (open ideo) to support a news challenge contest on open government. The platform allowed applicants to easily share their ideas and to solicit feedback from the community. Nearly 5,500 people signed up as ‘followers’ to monitor and engage with the projects submitted through the challenge.

In our arts challenge, a recent evaluation suggested we go even further in calling on community input in the contest. So we added to the contest a “people’s choice” award. We choose a short list of smaller arts organization finalists of similar sizes; and the people selected the winner by SMS text voting for their favorite. We didn’t use this method to judge institutional applications; it would be unfair for a small art collective, for example, to compete for public votes against an established opera or ballet with vast email databases.

Set clear expectations

for what it means to vote on or “like” an entry, so there’s no confusion in community voting. In particular, articulate how community input will relate to the final judging decisions.

Use external review panels.

Those might include members of the community you’re trying to reach, as well as former winners.

Make it the default option that applicants post their entries publicly.

In the news challenge applicants can opt to submit their entries privately, but generally over 90% of all submissions are posted publicly. Why? Because applicants see the benefits of attracting attention to their ideas and generating support.

In the wider world, contests are fairly common. Even Napoleon had one, a prize of 12,000 francs for a new method to preserve food for soldiers on the front, which led to canning. Today, a number of corporations and government agencies are running them — Netflix, IDEO, Google and even NASA. Many in the nonprofit world see contests as a passing fad, the philanthropic flavor of the month. We think they are here to stay. The McKinsey Report “And the Winner is” suggest they are catching on. The total value of nonprofit contest-prize growth over the past decade, the report says, has been 18 percent per year compared to 2.5 percent for general charitable giving.

Some foundations are doing stellar work in the field of contests. Those include the X-Prize Foundation, Case Foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, McArthur Foundation, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation, to name a few. But the vast majority of grantmaking foundations are not. Why? Is it inertia? Do they feel they don’t have the bandwidth? The expertise? Do they think their particular topic or issue just won’t work? Do they fear opening the flood gates?

In the end, contests, like everything else, can be as simple or as complex as you make them. Heather Bowman Cutway launched Macon’s “We’ll Leave the Lights On!” with just $2,150 from the community challenge. It was the contest format that made it easy for people like her to step forward with new ideas, which, Cutway says, “like light bulbs” can mean “big dividends.”

Download a pdf of the report

Download a pdf of the report