Why influence matters in the spread of misinformation

Becca Lewis is a Ph.D student in communications working at Data & Society. Below she writes about findings from a recent Knight report that explored how misinformation spread during the 2016 presidential election.

If you start paying attention to the issue of online disinformation, you will start to hear a lot about the role of “influence.” Most notably, media outlets have done widespread reporting on Russia’s so-called “influence campaigns,” meant to impact U.S. elections. But “influence” is an important online phenomenon more generally. If you use Instagram, for example, you almost certainly have encountered “brand influencers,” who build devoted audiences and then attempt to sell them products and services. Influence, then, is a crucial phenomenon online: it means having a powerful voice and using that voice to have an impact, whether political or commercial.

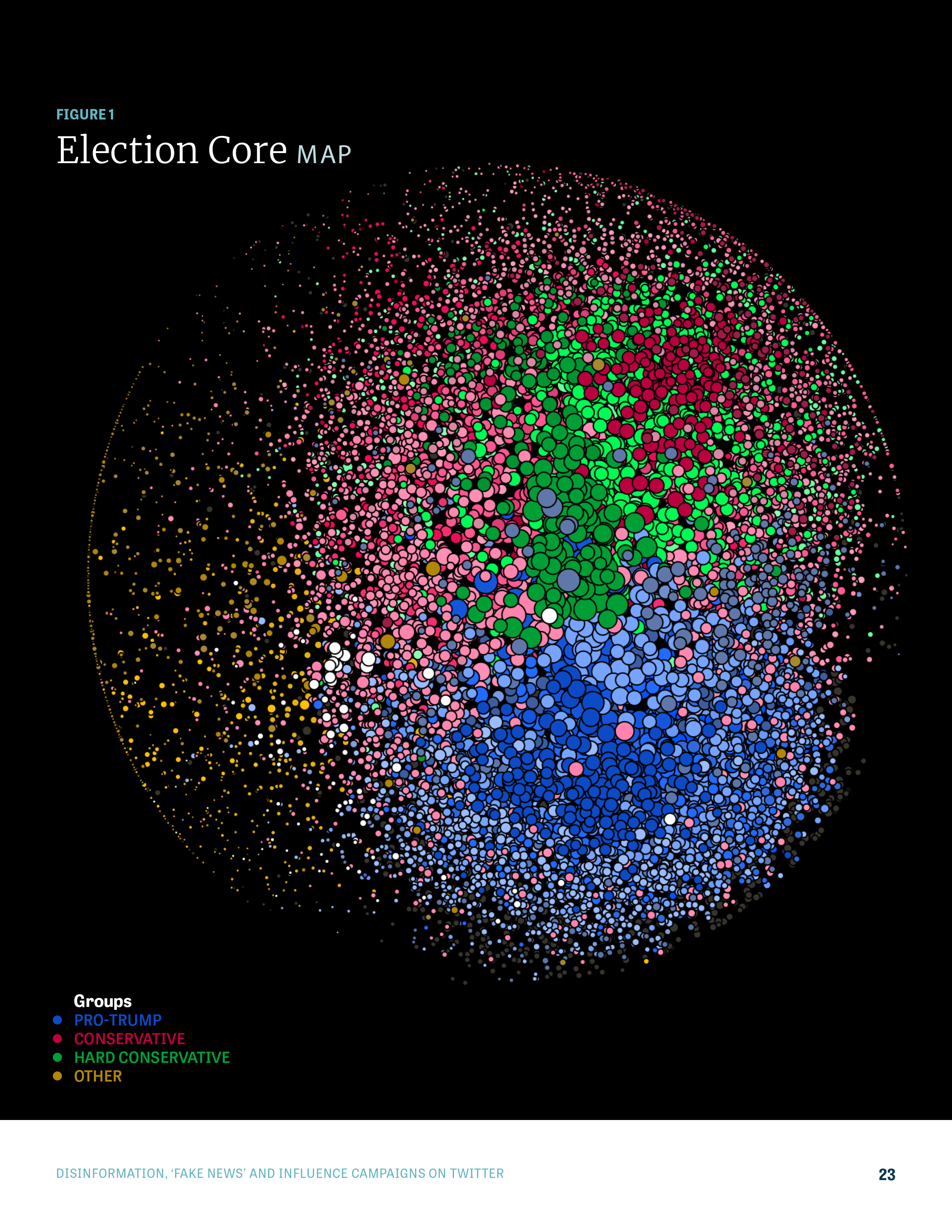

In a recent Knight Foundation report on how disinformation spread on Twitter ahead of the 2016 election, authors Matthew Hindman and Vlad Barash identified an “ultra-dense core of heavily followed accounts that repeatedly link to fake or conspiracy news sites.” In other words, they found that a few highly influential Twitter accounts played an outsized role in spreading conspiracy theories and disinformation.

This finding was striking for me. As a researcher of disinformation, hate speech, and political subcultures online, I have consistently found that influence plays a crucial role in disseminating harmful content. While Hindman and Barash focus on influential fake news sites, I research the role played by political influencers – that is, individuals with large followings who broadcast political content on social platforms.

Why is influence so important to the spread of disinformation and fake news? The answers are complicated, but I think there are at least two important factors.

Influential accounts can amplify fringe ideas and bring them into the mainstream.

In a 2017 report on media manipulation I co-authored with Alice Marwick, we argued that far-right influencers such as Richard Spencer and Milo Yiannopolous play a unique role in spreading disinformation and conspiracy theories. This is because they can amplify certain messages to their audiences and “make otherwise fringe beliefs get mainstream coverage.”

For one example of this phenomenon in action, we can look at the spread of conspiracy theories about Hillary Clinton’s health in the leadup to the 2016 election. In the summer of 2016, far-right bloggers began circulating conspiracy theories that Clinton was covering up massive health problems, based on an out-of-context video.

These theories mainly stayed within far-right circles until they were covered by Paul Joseph Watson, an influential YouTuber and editor for Infowars, in a video titled “The Truth About Hillary’s Bizarre Behavior.” After his video, the theories were covered by more mainstream outlets such as the Drudge Report and on Sean Hannity’s Fox News show. The more mainstream media outlets generally didn’t embrace the theories fully, but they still framed them as open-ended questions in ways that could seed doubts among readers and viewers.

Overall then, Watson helped bring the conspiracy theories from the fringe to the mainstream.

Influential accounts build trust with their audiences.

Influencers are also uniquely positioned to develop trust with their audiences. As Hindman and Barash note, studies have found that news consumers are more likely to accept news stories as true if they are shared by friends and family. In a report on YouTubers I released this September, I found that much like brand influencers, political influencers develop highly intimate relationships with their followers (even if those relationships are mostly one-sided). They may share personal stories with their audiences, post selfies on Twitter and Instagram, or broadcast a vlog from their bedrooms. At times, they may respond directly to their audience in YouTube comments or Twitter threads. Overall, they work hard to make sure the audience identifies with them, much in the way a friend would. Because of this, they don’t need a recognizable news outlet name or a team of fact-checkers to convince their viewers and readers that they are trustworthy sources of news.

In fact, I have found that a lot of the content posted by influencers isn’t even delivered in a way that can be fact-checked. Several white nationalist influencers, for example, tell deeply personal stories about their own radicalization (which they call “getting redpilled,” an illusion to The Matrix). These stories may very well be true, but they still often reinforce racist or sexist stereotypes and anti-Semitic conspiracy theories.

The Knight report focused on fake news outlets rather than influencers, but their findings resonate with my own. Specifically, they showed just how much disinformation on Twitter can be traced back to a few influential conspiracy theory accounts. It also reveals that these accounts can often build trust over time by posting just as much true content as false content. In other words, we have all found that influence plays an important role in the spread of disinformation and harmful speech on online platforms. With this in mind, we should be asking platforms if they know who is influencing the news on their sites, and how they expect to handle it.

-

Journalism / Article

-

Journalism / Article

-

Journalism / Article

-

Information and Society / Topic

Recent Content

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·