World premiere of Jennifer Higdon’s ‘Cold Mountain’ sparks excitement at Santa Fe Opera Festival

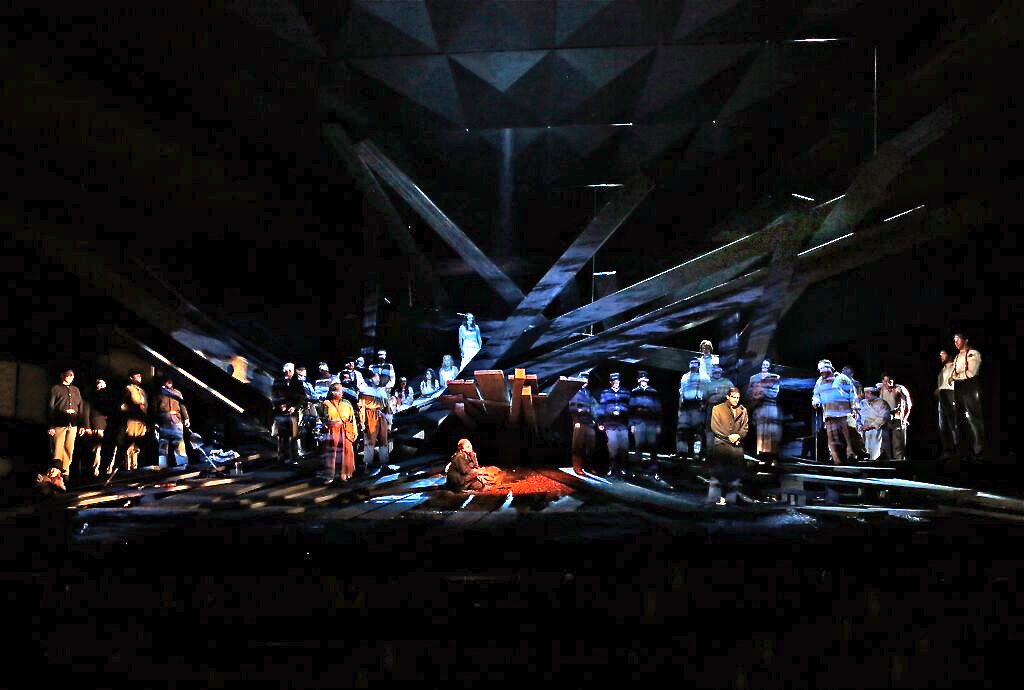

“Cold Mountain” by Jennifer Higdon. Photo by Ken Howard.

Stravinsky and Georgia O’Keeffe were right in going crazy over Santa Fe. In fact, they were as sane as the visionary John Crosby, who, fascinated with the New Mexico desert, decided to start an opera company in an environment where silence rivals music.

Crosby’s adventure in 1957 was highly successful, and today the Santa Fe Opera nears its 60th anniversary while enjoying worldwide prestige and generous support. Every July and August an international crowd converges on the spectacular outdoor theater nestled between mountain ranges for five operas, a season that includes rarities and premieres that delight critics and the public alike.

The undimmed star of 2015 was “Cold Mountain,” the first opera by Grammy and Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Jennifer Higdon, with a libretto by Gene Scheer, who happily summarized the essentials of the novel by Charles Frazier (it was made into a film by Anthony Minghella in 2003).

Isabel Leonard and Nathan Gunn in Higdon’s ”Cold Mountain” world premiere. Photo by Ken Howard.

The first act works as a sort of prologue, describing in flashbacks the odyssey of Civil War deserter W.P. Inman and his return to Cold Mountain where the preacher’s daughter Ada awaits him, a southern Penelope assisted by the rustic Ruby. In the second act, Higdon finds a more compelling language than in the first. Honest and conscious, she allows the voices to “breathe” in dialogues, arias and ensembles, while the symphonic moments allow a more conventional orchestral overcrowding. It is in the intimate instances and evocation of the Appalachian Mountains, folk songs and Southern lyricism, where both that world and the eagerness of the separated lovers is better reflected. The climax of the opera is the unforgettable chorus “Buried and forgotten”; it also marks a path for the composer to succesfully combine all the elements that make opera the great genre that it is.

The success of the world premiere rested on the shoulders of the seamless production by Leonard Foglia and a superlative cast under the direction of talented young Peruvian conductor Miguel Harth-Bedoya. Twenty-six singers sailed Robert Brill’s rightly oppressive setting, composed of interlaced planks and beams and transformed by the imaginative projections of Elaine McCarthy. The principals were superb; a restrained Nathan Gunn gave life to Inman and the radiant Isabel Leonard was absolutely ideal as “belle” Ada in a role that, like Massenet’s Charlotte, grows as the opera progresses. Kudos to the outstanding Ruby de Emily Fons and a sonorous Teague by heldentenor Jay Hunter Morris. They were well supported by Anthony Michaels-Moore, Roger Honeywell, Kevin Burdette, Robert Pomakov, and Deborah Nansteel as the slave Lucinda who frees Inman. It was a stellar lineup for an important premiere, and it deserves to be preserved on DVD.

Santa Fe Opera Theatre. Photo by Ken Howard.

“Rigoletto” provided a good night of opera. The crowded scene by Adrian Linford, served Verdi with a solvent cast where the jester of Quinn Kelsey shone. Young Georgia Jarman was a credible Gilda and Bruce Sledge an excellent Duke of Mantua under the inspired Jader Bignamini.

Mozart wrote the long and labyrinthine comedy “La Finta Giardiniera” when he was only 18. Here it was served by an exceptional ensemble, with great work by conductor Harry Bicket, who led an orchestra that was both refreshing and daring—and clearly connected to Mozart with its band of period instruments. The unpredictable Arminda of Susanna Philips joined was deliciously accompanied by William Burden, Joel Prieto and Joshua Hopkins. If the Serpetta from Laura Tatulescu stole the show, neither Cecilia Hall (Ramiro) nor the Countess turned gardener of Heidi Stober was overshadowed thanks to the shrewd direction of Tim Albery, the delightfully insane costumes of Jon Morell and the rococo settings by Hildegard Bechtler, who also wisely used the panorama of the sunset in the mountains.

Less fortunate was Donizetti’s “The Daughter of the Regiment,” a favorite vehicle for divos (Sutherland versus Pavarotti; Dessay versus Florez, etc). The version by Ned Canty proved that if it is difficult to create laughter in theater it is so much more so in opera, a genre where comedy requires perfect timing to avoid falling into ridicule. From the orchestra pit, the vigorous reading of Speranza Scappucci framed the farce onstage that seemed somewhat outdated and stiff. In that vein, Anna Christy (Marie) and Alek Shrader (with the “Ah, mes amis”) delivered. Fortunately, Phyllis Pancella drew her Marquise without the usual tics, which complemented the Sulpice of Kevin Burdette.

“Salomé.” Photo by Ken Howard.

There was a timely return to drama with Richard Strauss’ “Salomé”; the rendition by Daniel Slater was set in the period of Oscar Wilde with an imposing Herodias (Michaela Martens) quasi Queen Victoria. The set by Leslie Travers was an impressive giant metal crate, serving as a terrace, palace and library/cistern where Iokanaan (a splendid Ryan McKinny) embodied a febrile philosopher that has run out of time. Robert Brubaker was in charge of a sordid Herod, while tenor Brian Jagde (Narraboth) is assuredly a new name to follow.

Slater changes the dance of the seven veils with a revealing Freudian racconto of the Princess’ childhood, including the abuse by her uncle, her father’s killer. The Bulgarian Alex Penda was a passionate Salome, but one whose incisive Slavic timbre lacked Wagnerian opulence for that impossible “16-year-old Isolde” required by the composer. David Robertson triggered a volcanic reading of the orchestra but also evoked that fabled phrase attributed to Strauss, “Louder! I can still hear the singers.”

The Santa Fe Opera Festival is an irresistible event in a magnificent setting, enjoyed by both aficianodos and casual observers commenting on what they saw the night before. It is a tempting invitation to return each summer to the place where Stravinsky and O’Keeffe “logically went crazy.”

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·