Concert Will Explore Secular, Sacred Sides of Bach

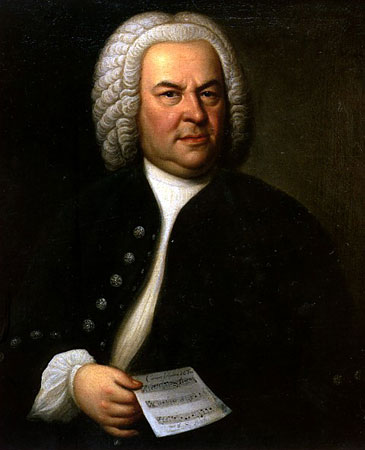

J.S. Bach (1685-1750). Peter Schickele once wrote that he’d be happy to give up some J.S. Bach cantatas for a few more Brandenburg concerti, even though he knew that was as close to heretical a statement as you could make.

Beginning Friday, you can have both, when the Firebird Chamber Orchestra begins its Brandenburg Concerto project, playing all six of these timeless works over a three-year period. This weekend’s concerts also include one of the cantatas, as well as the best-known of the orchestral suites.

The program for the weekend has changed somewhat from earlier announcements. We’ll hear Concerto No. 3 in G, notable for its brevity and catchiness, and No. 5 in D, singular because it really is a harpsichord concerto more than anything else (Olukola Owulabi, a Canadian-born professor at the University of Syracuse, will do the honors for the Firebird).

We’ll also hear the Cantata No. 84, Ich bin vergnügt mit meinem Glücke (I am content with my fate), with soprano Kathryn Mueller as soloist. The concert is rounded out with the Orchestral Suite No. 2 in B minor, which is famous for its Badinage final movement, a staple of the flute repertoire.

The interesting thing here, besides finally getting to hear the Brandenburgs done locally, is that it represents the two sides of Bach’s composing career. The Brandenburgs (named for a margrave who didn’t do much to acknowledge the gift of these pieces) and the orchestral suite date from the composer’s time at the court of Cöthen, where his music-loving boss gave him just about everything he needed to create good music for the daily life of the palace.

Up until the point that he left for Leipzig in 1723, where he became a church musician and school official, and where he would spend the rest of his life, Bach was writing a very powerful kind of secular music, far more elaborate and advanced than the work of contemporaries such as Telemann, good as they were.

Bach left Cothen in part because the prince’s new wife didn’t much care about music, and the budget cuts spurred Bach to seek his fortune elsewhere. But what if he’d found a post similar to his old job and kept writing in the style of the Fifth Brandenburg Concerto? It could well be that he would have inaugurated the era of keyboard concerti that didn’t really take off until the innovations of Mozart some 60 years later.

And would he have composed opera, as he was expected to do? His great contemporary George Frideric Handel, born the same year, was a man of the theater and found plenty of fame and fortune on the stage and later in oratorio. Domenico Scarlatti, also born that year, became the true keyboard innovator, writing hundreds of “exercises” that break new ground in harmony and technique.

Bach came close with the St. John and St. Matthew passions (his setting of the St. Luke Passion is lost), and some of the more elaborate cantatas are close to opera. But in general, he served the church and the needs of the students at St. Thomas, and that turned him primarily into a sacred music composer. John Eliot Gardiner in England took his Baroque ensemble to Europe and New York for a Bach cantata pilgrimage 10 years ago that opened people’s ears to the richness and beauty of these great pieces of music.

And yet there will always be some who would have preferred to hear more secular Bach than sacred, and who always will wonder what might have been. I personally love it all, but I can understand that point of view, and it will be enlightening to hear both major sides of this composer’s art this weekend.

The Firebird Chamber Orchestra performs at 7:30 p.m. Friday at First United Methodist in Coral Gables; at 8 p.m. Saturday at All Saints Episcopal in Fort Lauderdale; and at 4 p.m. Sunday in the Temple Emanu-El in Miami Beach. Tickets are $35. Call 305-285-9060 or visit www.seraphicfire.org for more information.