InLiquid tackles the monster of the juvenile justice system at Crane Arts

Crane Arts is in the midst of a vast exhibition organized by InLiquid that explores and ignites discussion about the challenging and often overlooked world of juvenile detention and youth incarceration.

“Juvenile In Justice” comprises work by three artists: Richard Ross, Roberto Lugo and Mat Tomezsko, which each approaching the topic from different but relevant angles. There is also a wide range of programming in the space to accompany the show, including film screenings, panel discussions and a youth art show opening.

This formidable project seeks to break down the barriers that often exist for outsiders to understand exactly what goes on inside the juvenile justice system in this country, and advocates for creative arts and positive social change to reform these institutions. “Juvenile In Justice” seeks to raise $30,000 throughout the course of the show to expunge the juvenile records of some 150 individuals. On Dec. 3, the exhibit will cap off with #GivingTuesday – a socially conscious alternative to consumer spending on Black Friday and Cyber Monday.

This exhibition sets some serious goals: to raise awareness of this national issue and what Philadelphia is doing to improve juvenile justice systems; to give the community’s youth a voice through a Youth Ambassador Program; to provide a platform for local organizations to share their programs and resources; and to break the school-to-prison pipeline that exists in the current political climate.

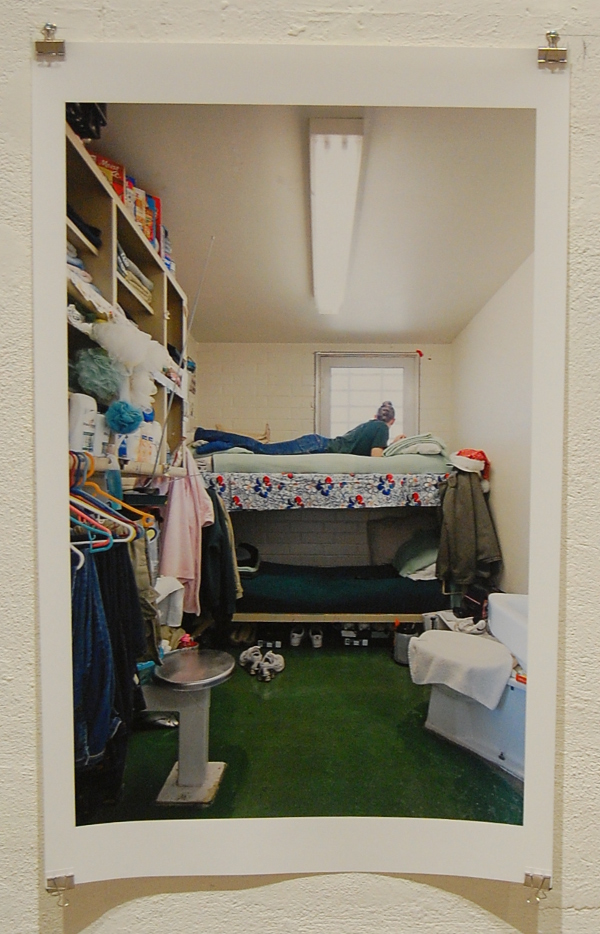

Richard Ross, “Mendota Juvenile Treatment Center, Mendota, Wisconsin, 1.”

In the Ice Box space, Richard Ross provides a lens and a story for those who would otherwise slip through the cracks of our social consciousness. Since 2006, he has traveled the country, visiting more than 250 juvenile detention centers to document the experiences of those who inhabit their cold walls. In the center of the space, there is a “solitary confinement” room built specifically for the show. Only one chair sits in the tiny room, which recreates the area that many children who are taken into custody first experience.

Richard Ross, “Ventura Youth Correctional Facility, Camarillo, California, 2.”

All of the walls around this central facility depict the reality of living in such a place. A girl arrested at 13 for a botched burglary sits in a concrete living quarters decked out in personal effects as she peers out the window. She is now 20 and expects to call this cell home potentially until she turns 25, only leaving to participate as the head of a women’s firefighting unit. Elsewhere, boys with shaved heads in yellow jumpsuits stand before an officer in a wide-brimmed hat, and cuffed hands hang out of a blue, metal door. If this is the way we treat our troubled youth, one can certainly only expect more trouble.

Mat Tomezsko, works from “There Is No.”

Mat Tomezsko’s series, “There Is No,” consists of 94 prints created in response to the death of a friend. They demonstrate The Ninety-Four Effect, which states that for every person killed, 94 people are directly affected. The text and layered colors are undeniably grim; sometimes they resemble faces, other times pools of blood. Tomezsko reminds us that we should judge our society’s worth by what the poorest among us possess, not the middle class that politicians are so quick to glorify. Inescapable poverty not only allows for such violence to flourish, but oftentimes defines the lives of those who have no way out; it is truly a symptom of a sick society.

Roberto Lugo, “Bloods and Crips/Democrat and Republican ‘We’re Not That Different.'”

The story of Roberto Lugo is one of utilizing art to realize another way. Raised in Kensingon, often cited as one of Philly’s roughest neighborhoods, Lugo watched as many people he knew headed to prison or worse. By turning first to graffiti art, and then to ceramics, Lugo discovered a constructive way to draw himself away from destructive surroundings. His work often references the topics of gangs, racism and violence, which he narrowly avoided. Lugo is currently a graduate student at Penn State University.

By directly confronting the issues at hand in poor communities and in the often dehumanizing and humiliating system of youth detention, we can begin to change the behaviors that only beget more violence by supplanting them with productive and forward-thinking projects. There is no time like the present to engage in such a conversation, because for some, it’s already too late. Visit “Juvenile In Justice” at the Crane Arts Building through Dec. 12.

Crane Arts is at 1400 N. American St.; [email protected]; cranearts.com

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·