An astonishing night of Cage at the New World

There are concerts and there are concerts, and then there are explosions of art, bursts of concentrated, disciplined energy that sweep in like a wind and leave everything leveled and changed.

Such was the performance I saw Feb. 9 at the New World Center of John Cage’s Song Books, an astonishing experience of precisely 46 minutes that reimagined the concert enterprise in a remarkably original way and at the same time made a persuasive argument for the centrality of Cage to the idea of artistic freedom.

To say that it was more performance art than concert is to try to fit it into a category it doesn’t want to occupy in the first place, and hinders its peculiar attractiveness: Following a mind going off on a kind of highly organized random journey, in which the answer Why not? is chosen more often than not, and in which there is no real discourse except the act of discoursing itself, and no point of arrival, just an ending, which while clear suggests in its very finality that this was just one of an infinite myriad of conclusions.

The Song Books was on the second half of the second of the three concerts at the New World devoted to Cage’s music in the seasonal observation of the centennial of his birth in 1912. The first half featured a performance of Cheap Imitation, a recomposition of elements from Erik Satie’s Socrate, accompanied by the ballets Second Hand and Enter, choreographed by Cage’s life partner Merce Cunningham.

The three-movement Cheap Imitation is derived from the vocal line of Socrate, transposed up and down or run through different modes; Cunningham’s original dance had used the actual Socrate, but Cage could not win the rights from Satie’s publisher to arrange it for smaller forces, and so echoed it in this manner while staying faithful to its contours, which saved Cunningham the trouble of having to scrap it and do something else.

Andrea Weber and Brandon Collwes in “Second Hand,” danced to John Cage’s “Cheap Imitation.” Photo by Rui Dios-Aidos

Brandon Collwes and Andrea Weber, both veterans of Cunningham’s company, were the two dancers for the three movements (the original 10-dancer third movement was restructured to include choreography from Enter). The music is largely unvaried, in a macro way, throughout; it has the same basic tempo and moderate-volume from start to finish. The second movement was played by Cage himself on film (he died in 1992), playing the piano in the same steady style.

After a while, the music took on a sort of white-noise pleasantness, an unbroken, eternal line that seemingly started at some point long before the evening began and likely is going on still. It served as an effective backdrop to the dance, which was a series of stretches and poses reminiscent of tai chi and yoga, and which looked quite difficult to do.

Both dancers are in enviably good physical shape, as you would expect, and of the two, Weber seemed somewhat looser and more flexible. Her movements – both dancers wore simple leotards – were mesmerizing, pure expressions of a body responding to inner compulsion, writing the poetry of the human machine, drawing focus too on detail: Two feet prepping for a lift, a curved hand, a bent back.

Andrea Weber and Brandon Collwes perform in front of the New World Symphony and beneath archival footage of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Photo by Rui Dios-Aidos

In the two outer movements, the musicians of the New World Symphony performed the score, offering fragments of color as the orchestration changed with each phrase. In their shared stripped-down aesthetic, Cheap Imitation and Second Hand constitute the profoundest kind of hommage to Satie, a deeply felt rendering of the idea that less is more, and in this case, that less just is.

The Song Books, which date from 1970, is essentially a theatrical compendium of song and instrumental fragments married to Dadaesque stage business, in which much the most memorable line is that taken from Thoreau: The best kind of government is no government at all, and that is what we will have when we are ready for it. Some of the songs are actual short pieces of music, some of them are activities, such as a person walking on stage in a giant costume man’s head. The songs come and go, starting when and where they like, and the overall effect is one of furious, impish invention, a kaleidoscope of ideas absolutely untrammeled by any sort of directive except one: Let’s go make some art.

Michael Tilson Thomas, who spearheaded this tribute to Cage, has to be credited with putting together one of the most respectful, intelligently prepared celebrations of this singular artist’s work of anyone, anywhere that I’m aware of. It’s not too much to say that these three days (and Saturday night in particular) were something of a milestone for Miami as a culture-minded city. Something like Song Books could only be performed in a city that has reached a cultural critical mass, and that it came off so well says impressive things about South Florida’s artistic development.

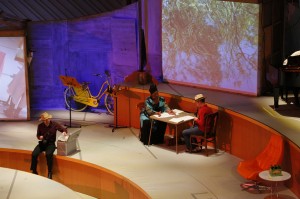

Michael Tilson Thomas and New World fellows perform in John Cage’s “Song Books.” Photo by Rui Dios-Aidos

But Tilson Thomas is also a performer, and he was a fully committed member of the company that gave Song Books, a company that included stellar performers such as singers Jessye Norman and Joan La Barbara, pianist Marc-Andre Hamelin and composer Meredith Monk. They were joined by 12 New World fellows, all of whom played their various parts with enthusiasm and dedication.

The stage at the New World Center had three mini-stages at the rear with panels that served as screens for film or opened to reveal something inside, which changed constantly: Jessye Norman, singing; a man selling bird cages underneath a purple sign reading GIFT SHOP; Joan La Barbara writing at a desk; a man crouching to the ground and looking out on an unseen prairie for trouble ahead. The film fragments included snow falling near a cabin, and shots of things that had just been seen but were now being mixed up, such as a particularly brilliant bit in which a man spelled out “Marcel Duchamp” on flash cards, which were then rebroadcast in reverse and then in random order.

At the side were two pianos at which Hamelin and pianist Marnie Hauschildt played bits from Cage’s Winter Music for piano, mostly clusters and angular phrases (the pianists’ hands were filmed and replayed on the screens as well). It was all part of a larger theatrical motion in which there were various bits of silliness such as Tilson Thomas chopping vegetables and sticking them into a blender, or sitting in a suit jacket covering himself in Post-It notes. At any one time, there were at least five or six different things happening, only some of them singing: A trombonist marched in, playing something parade-like; a cellist and a violinist traded phrases; a man in a hat bounced around on a pogo stick; a newspaper was torn into long strips.

Meredith Monk in John Cage’s “Song Books.” Photo by Rui Dios-Aidos

Norman, Monk and La Barbara did most of the singing, and Norman happily showed that she is incapable of singing anything without making it sound beautiful, and it elevated all of the music in the score. At one point, Monk came downstage to repeat the Thoreau line numerous times, and one of the three stages opened to show Tilson Thomas and nine other men singing the same line loudly and forcefully, like a group of militant protesters on their way to man the barricades. Over it all, two black flags of anarchy waved in an artificial breeze, and at precisely 46:00 the performance came to an abrupt end as Tilson Thomas tossed aside a rolled-up newspaper ball.

The hall was full of leading Miami arts figures, and they and the rest of the audience are unlikely ever to forget what they saw. It was nothing short of amazing, and it’s also not likely that you would be able to see it again live (it was being recorded for online presentation), or ever see it done this well again. The audience gave it a ferocious acclimation, and it was well-deserved.

Strangely enough for someone considered to be an artist eternally mocking the pieties of his time, both these pieces showed Cage’s admiration for Satie and Thoreau, creators as original and inimitable as Cage was. People seeking to understand Cage by looking at musical predecessors and contemporaries such as Stravinsky are looking in the wrong place.

Cage belongs to that most rarified of all creative heritages, that of the entirely unafraid artist, listening only to his inner promptings and following it whatever the cost, without compromise, because to do anything else is not to be an artist. Like them, too, he is unlikely to ever enjoy widespread popularity, but his example, like theirs, is immense and permanently salutary for those who wish to dedicate their lives to the artistic enterprise.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·