Bringing poetry to people in a free, open, accessible, physical, lasting way

The Wall Poems of Charlotte projects helps bring poetry into everyday spaces, and just finished its second work. Here, founder Amy Bagwell writes about why and how the Knight-funded effort got started.

That fewer than 10 percent of American adults read or listen to poetry in a given year is not a failure of the people. If we substitute the word encounter in that statistic for the words read or listen to, we begin to get at it.

It’s about access. Poetry, like jazz, has been expropriated so that it seems almost solely the realm of the affluent, the hyper-educated. This blood-and-guts expression, like jazz, is a something that feels remote to most people. Dead.

My creative partner Graham Carew and I were lucky. Poems have been available to us all our lives. My mom had Rod McKuen records when I was a kid. These weren’t poems I fell in love with (that started with E.E. Cummings), but they were poems, and they were in my house. Graham grew up in Ireland, blessed with a culture that appreciates and emphasizes broadly its poetic heritage.

Today, poetry is published too little and at a loss, and it’s left to slim, hidden shelves in box stores, and it’s taught, as Tony Hoagland has so eloquently and hilariously examined recently, abysmally—as autopsy, even when we have the best intentions.

And the crime in all of this is that poetry, which can be transformative, belongs to everyone.

Poetry is an action, and this is a fact I keep in mind. —Yusef Komunyakaa

We like to think that our work in Charlotte with Wall Poems is an action in response to poetry being gone from most of our lives. We’re directly inspired by the 101 Leiden Walls in Holland, poems painted in their native languages by a trio of genius activists and artists (who offered us generous, keen advice when we visited last January.) Our friend and mural artist Scott Nurkin, of The Mural Shop, paints the poems on walls, an act of magic on the eccentric, gnarly, terraced, weather-chewed surfaces we often address. And we’re now working on two metal pieces as well. The designs are created in 3D as interpretations of the poems and as extensions of the lives (present and past) inside the walls they’re on, adjacent to them, across from them.

We’ve just finished our second Knight-funded Wall Poem, both of which were designed by Cynthia Frank, a graphic designer who teaches with me at Central Piedmont Community College. All our poems are by North Carolina writers. The first, “First Novel” by Fred Chappell, is a blue stunner painted on the wall of a car rental office across from the UNCC Center City Campus. Only about 13-feet tall, it can be read in the photo.

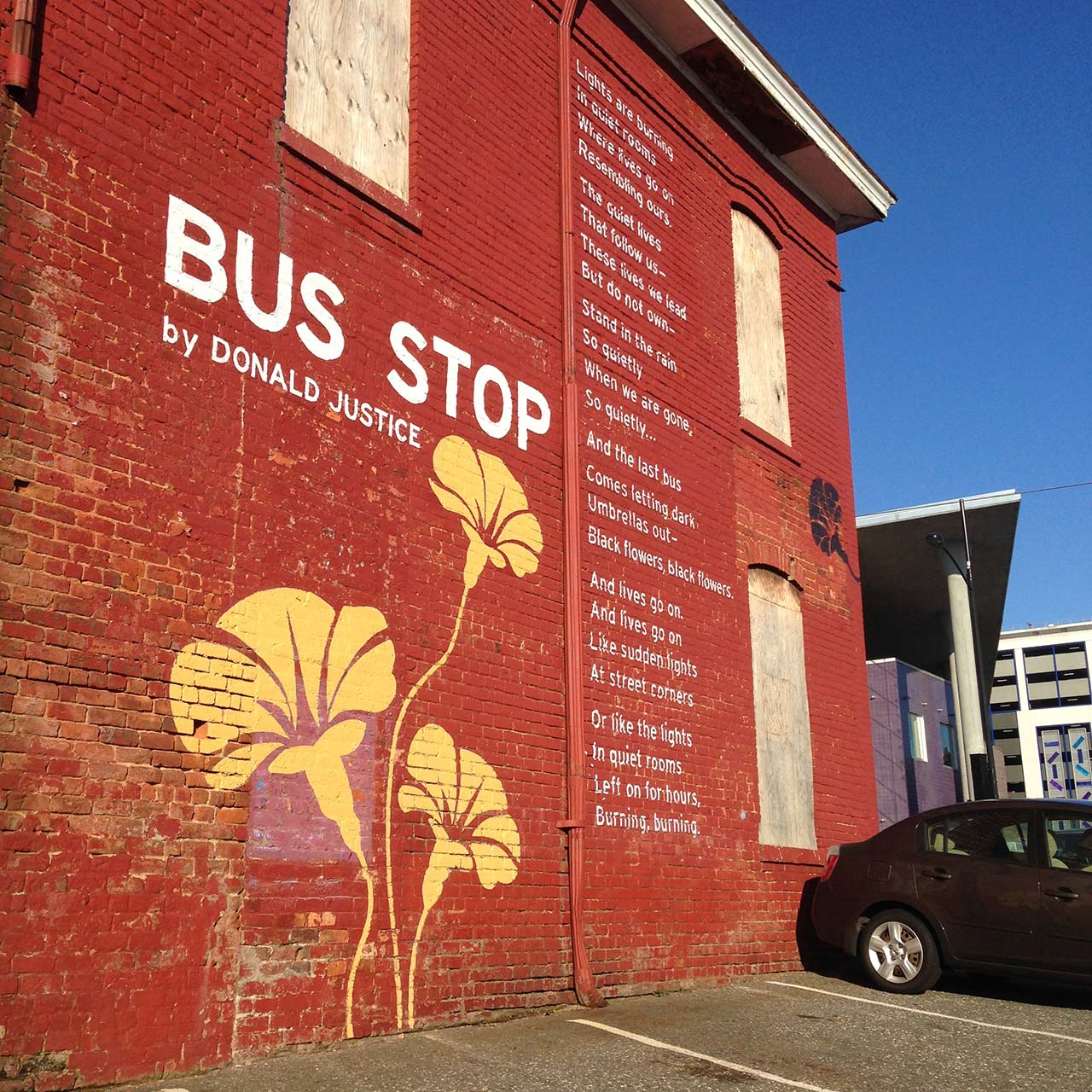

The second is this gut-punching, echoing wonder of a poem:

Bus Stop Donald Justice

Lights are burning In quiet rooms Where lives go on Resembling ours.

The quiet lives That follow us— These lives we lead But do not own—

Stand in the rain So quietly When we are gone, So quietly . . .

And the last bus Comes letting dark Umbrellas out— Black flowers, black flowers.

And lives go on. And lives go on Like sudden lights At street corners

Or like the lights In quiet rooms Left on for hours, Burning, burning.

After several weeks of merciless brick, lift mishaps, starts and stops, and hateful August heat (as I said, this is an action), the poem is now a part of the historic Treloar House, built in 1887 for an English immigrant gold miner and entrepreneur and one of only two surviving Victorian row houses Uptown. We’ve got words and images on all four sides of this old, boarded-up building.

We hope we’ve given the poem a proper treatment on a fitting stage. And we hope that folks will see it and know it is theirs: people passing on foot and in cars; going in and out of the children’s library, Imaginon, next door; visiting First Ward Park across the street (when it opens); heading to games or shows at the arena, from which it can be seen; commuting on buses and the train, which stops a short block away; and everyone else.

All of the poems are theirs.

And we are grateful to be allowed, enabled (by so many supporters and cheerers), and even invited to show that this is true in a free, open, accessible, physical, lasting way.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·